You Have Been Assigned the Anti-Discrimination and Discriminatory Harassment Policy and Procedures for Students Training Course

Did you complete it?

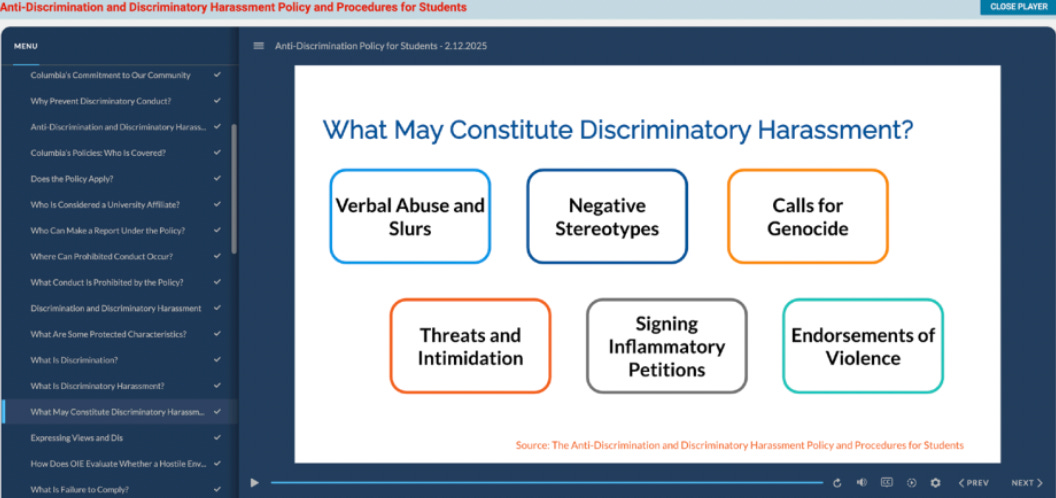

Under Columbia’s new anti-discrimination policy, you could be punished for signing petitions if they happen to contain “inflammatory language about a protected class.”

This comes from the new “Anti-Discrimination and Discriminatory Harassment Policy and Procedures for Students” training that Columbia’s Office of Institutional Equity (OIE) mandated for all University affiliates this semester. The policy, which is often overly vague, will only inflame an already tense campus rife with debates about the limits of free speech.

While it is admirable that OIE is taking steps to address rampant discrimination on campus, the policy’s wording does little to address the problem of antisemitism and other forms of discrimination—all it does is put free expression at risk.

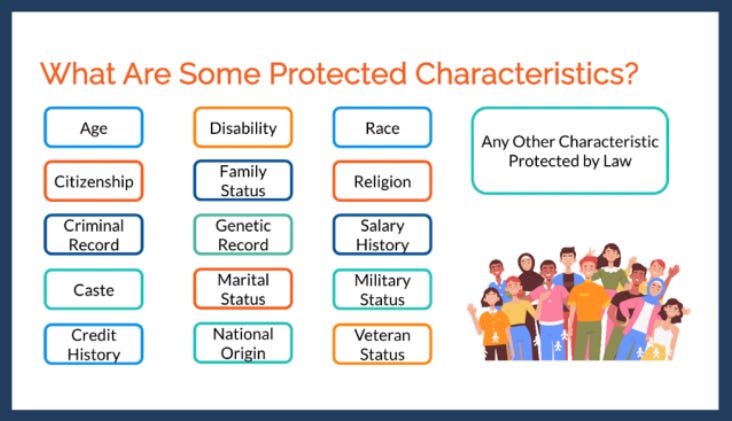

First, OIE takes a very broad and subjective approach in defining what constitutes a “hostile environment,” which Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibits on university campuses. Per University policy, if an environment is “subjectively and objectively offensive,” it can be considered a “hostile environment.”

First, the “objectively offensive” part raises a number of issues. For an environment to be “objectively” offensive, it has to be “hostile when viewed from the standpoint of a reasonable person,” which can include the use of “slurs, threats, and jokes that denigrate one or more members of a protected class.” At first glance, this seems like a concrete standard to evaluate campus speech, as we may have previously assumed that most students would find these things offensive.

However, as the events of the past few semesters have shown, this is far from the case. We come from a wide range of backgrounds and have different thresholds for what we consider “hostile,” thresholds shaped by religious beliefs, political leanings, and other factors. At Columbia, it is impossible to define a “reasonable person.”

For instance, the word “Zionist,” at its core, is a neutral word describing those who believe Jews have the right to self-determination in the land of Israel. But many have taken it to be a derogatory replacement for “Jew” and have argued that students should face punishment for criticizing or protesting “Zionists.”

How can we distinguish between the derogatory use of “Zionist” and the neutral use of “Zionist”? What if someone using the term in the neutral sense, with no intention of harming anyone, offended some Jewish students but not others? Which group should the University defer to?

When Columbia College student Khymani James said last year, “Be grateful that I’m not just going out and murdering Zionists,” does that create a hostile environment? Does it matter that he only said it online during a livestream rant? Does it matter that he later said he distinguishes between antisemitism and anti-Zionism?

By the same logic, what if someone described groups like Hamas and Hezbollah as terrorists, and, despite having no intention of harming anyone, offended some Palestinian students, but not others? Where will Columbia draw the line?

We are already seeing the effects of overbroad speech policies with the arrest and potential deportation of Mahmoud Khalil. While pro-Israel advocates viewed the encampments of 2024 as hostile and threatening, a pro-Palestinian protestor would vehemently disagree and might even describe it as a “peaceful” community. Both sides have reasonable arguments for their views, which creates a massive disconnect: Not all “reasonable” people see things the same way, and OIE’s policy fails to account for that.

This is in no way a defense of Khalil’s conduct and rhetoric. Some of it (including his support for “armed resistance” and involvement in pro-Hamas rallies and illegal takeovers of Barnard buildings) could be reasonably perceived as “threatening” by many. It could also be interpreted as supporting terrorism, which is grounds for deportation even for permanent residents under the 1952 Immigration and Nationality Act.

But in gray areas like this, the outcome is entirely determined by the party that gets to decide whether certain speech indeed endorses terrorism. Khalil’s case illuminates the problem with attempting to create an objective standard for hate speech or violent speech.

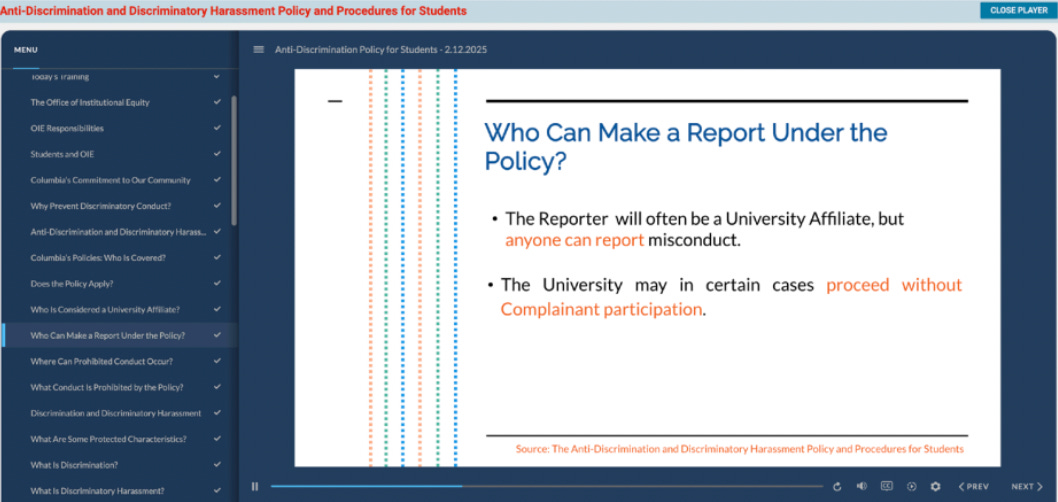

Second, the policy’s consideration of whether speech is “subjectively” offensive raises similar issues. The training defined this as a situation where “individuals must actually experience the environment as offensive.” Crucially, the training also stipulates that an individual does not need to be the subject of harassment—or even be present when it happens—to file a report.

In other words, if just one person felt attacked by what someone said—even if the speaker did not intend it that way—that person can file a report to OIE. “Stereotypes or slurs about individuals who identify with a particular race,” the training states, “can create a hostile environment even when the speaker does not target such individuals.” This constant threat of discipline will encourage others to self-censor when controversial political topics arise, eliminating any constructive dialogue on those issues.

The policy goes even further: The reporter “could be someone who reports on the complainant’s behalf.” In other words, given the increasing reach of digital content, almost anyone can file a report with the OIE—even if their knowledge of the event is inaccurate or lacks context.

Students, professors, and administrators could easily abuse this policy to effectively act as Columbia’s unofficial tone-police. In the most nefarious of situations, one could simply lie about a disfavored student’s conduct or speech. The possibility for exploitation of the policy is bound to make things worse for students in an already poor free speech climate.

Don’t get me wrong: some form of new anti-discrimination training is needed. Nevertheless, OIE’s is so broad and vague that it risks substantially chilling campus dialogue. Even if most speech wouldn’t run afoul of the policy, just the threat of burying someone in accusations is enough to make them think twice before speaking up. And all for what? To protect the University from controversy?

As productive conversations become even more elusive, students will lose trust in the University and each other. Columbia’s responsibility is to educate, not to adjudicate our interpersonal disputes. Although policies like these may arise out of good intentions, no amount of mandated training can ever replace healthy dialogue.

Mr. Engel is a senior at Columbia College studying history and a senior staff writer for Sundial.

You make a lot of semantic distinctions. Very fancy stuff, cutesy for the academics, but totally out of place in a civilized setting. The word "murder" and the physical act of takeover of Barnard are not subtle distinctions involving word play. They are serious words that have no place at a university.

The “reasonable” standard is a cornerstone of common law legal principles. It’s up to an adjudicator (judge or jury) to determine whether particular consequences could reasonably be expected to flow from conduct or speech. Each side in a dispute will have its own view of whether the reasonableness standard has been met. Ultimately, the adjudicator will decide.