Should We Trust the FIRE Rankings?

A conversation with FIRE’s Chief Research Advisor Sean Stevens on his organization’s free speech rankings

It has become something of a truism that free speech is in short supply in Morningside Heights. Just about everyone is asserting it. But can we quantify how bad the situation is? According to the College Pulse and the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE)’s College Free Speech Rankings, the situation could not get much worse. Ranked according to its “free speech climate,” Columbia placed 256th out of 257 American colleges and universities considered in the analysis. And who was in last place? None other than Barnard.

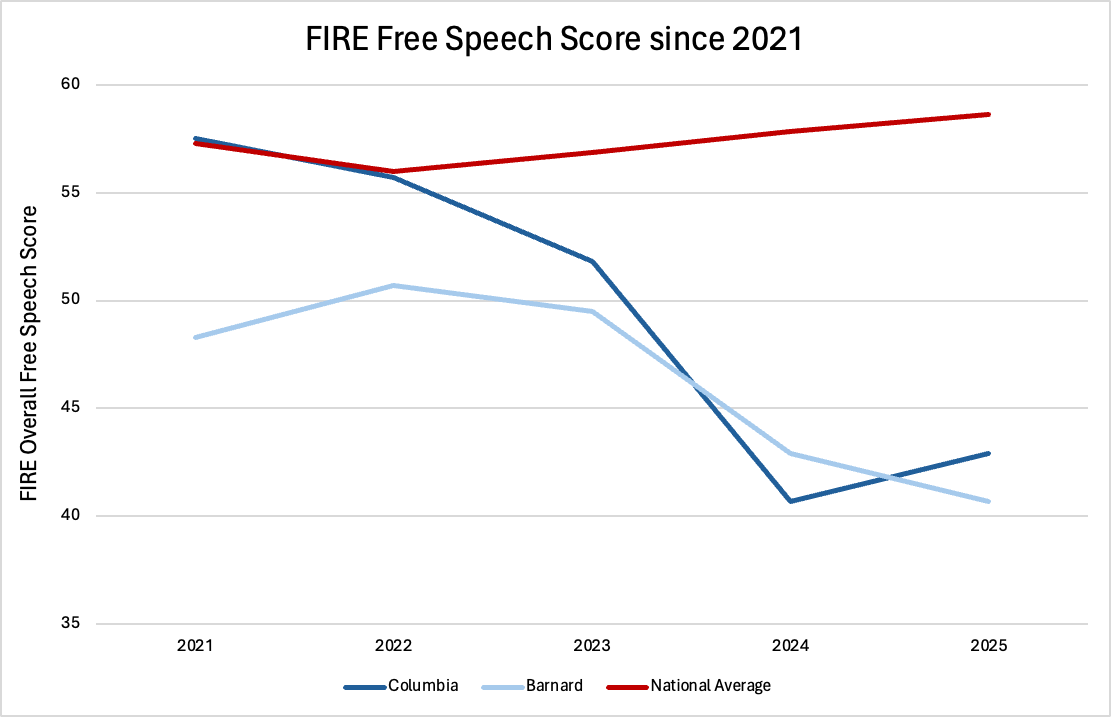

The results are disappointing yet unsurprising to many. It’s the third time in the last four years that Columbia has ranked in the bottom two. Additionally, Barnard fared worse than its 5th-to-last-place finish in last year’s report. The overall free speech scores for both have nosedived since the October 7 attacks, even as the average score for America’s colleges has actually increased.

Free speech is surely scarce on both sides of Broadway, but not all students agree with the accuracy of FIRE’s results. Sundial staff writer and photographer Jonathan Perry, for example, accused FIRE last month of “sensationalism” and of using its survey findings as “a powerful tool for generating moral panic.”

It’s natural to question the motives behind the data and methodology used to quantify a topic as subjective as “free speech,” especially during a particularly tumultuous time in the University’s history.

How can we trust and interpret FIRE’s assessment of free speech on campus? Who are they funded by? Are there certain trends and stories buried within the data? To answer these questions, I spoke with FIRE’s Chief Research Advisor Sean Stevens.

Founded in 2000, FIRE is a nonprofit “committed to defending and sustaining the individual rights of all Americans to free speech and free thought.” Among their top donors are a variety of foundations across the political spectrum, from the right-leaning John Templeton and Charles Koch Foundations to the left-leaning Knight Foundation and Bloomberg Philanthropies.

“The rankings factor in survey data from 68,000 students, data on speech codes, and the different databases that FIRE maintains about free speech controversies on campus in determining an overall score,” Stevens told me.

“One alarming finding is that student acceptance of political violence is at a record high.” According to FIRE, whereas just five percent of students in 2022 found it “always” or “sometimes” acceptable to “use violence to stop a campus speech,” that number has now jumped to 15 percent.

In the wake of the Charlie Kirk assassination, these numbers are telling. Perry, however, rejects its concerning nature. He argues that a student answering this question is much more likely to imagine the acceptability of “punching a literal Nazi” rather than “the assassination of a mainstream conservative speaker,” thereby making this finding “intellectually [dishonest]” to present.

On the one hand, Stevens actually agreed, telling me, “I’d be very surprised if that number didn’t decline next year. Most students weren’t thinking of that [Kirk’s murder].” This being said, the problem is where we can draw the line between acceptable and unacceptable acts of political violence, or whether such violence is acceptable at all. While many viewed Kirk as a mainstream conservative, others saw him as a literal Nazi. After all, several Columbia Sidechat users, as well as the Columbia Federalist, offered jokes and praise for Kirk’s murder based on his beliefs.

Violence often begets further violence. Hypothetically, if I attacked someone because I don’t approve of their beliefs, it would open the door for someone else to do the same to me. To that end, I would fault the “imagination” of the student that Perry hypothesizes more than the wording of the question.

Still, I asked Stevens to go a step beyond the abstract numbers in explaining what’s gluing Columbia and Barnard to the bottom of the rankings. As it turns out, a central factor is how the administration has dealt not with students, but with its faculty and staff.

“A concerning pattern for Columbia and Barnard is that they have a lot of entries in our ‘Scholars under Fire Database,’” Stevens replies, “especially the number of sanctions against their faculty members from their own administration.”

The database reports 12 separate instances of faculty and staff being investigated, censored, or even forced to resign by the Columbia Administration since the October 7 attacks. It includes well-known figures such as Joseph Massad, Rashid Khalidi, and Shai Davidai, but also lesser-known incidents such as the termination of Public Health Professor Abdul Kayum Ahmed for referring to Israel as a “settler colonial state,” as well as the investigation into PhD student Daniel Di Martino for sharing social media posts critical of transgender identity.

Glossing through it, I was amazed by how the administration, acting through a variety of offices, councils, and authorities, managed to censor and silence both left and right-leaning faculty voices. Simply put, it seems Columbia’s administration has completely abandoned any sort of principled approach to free expression.

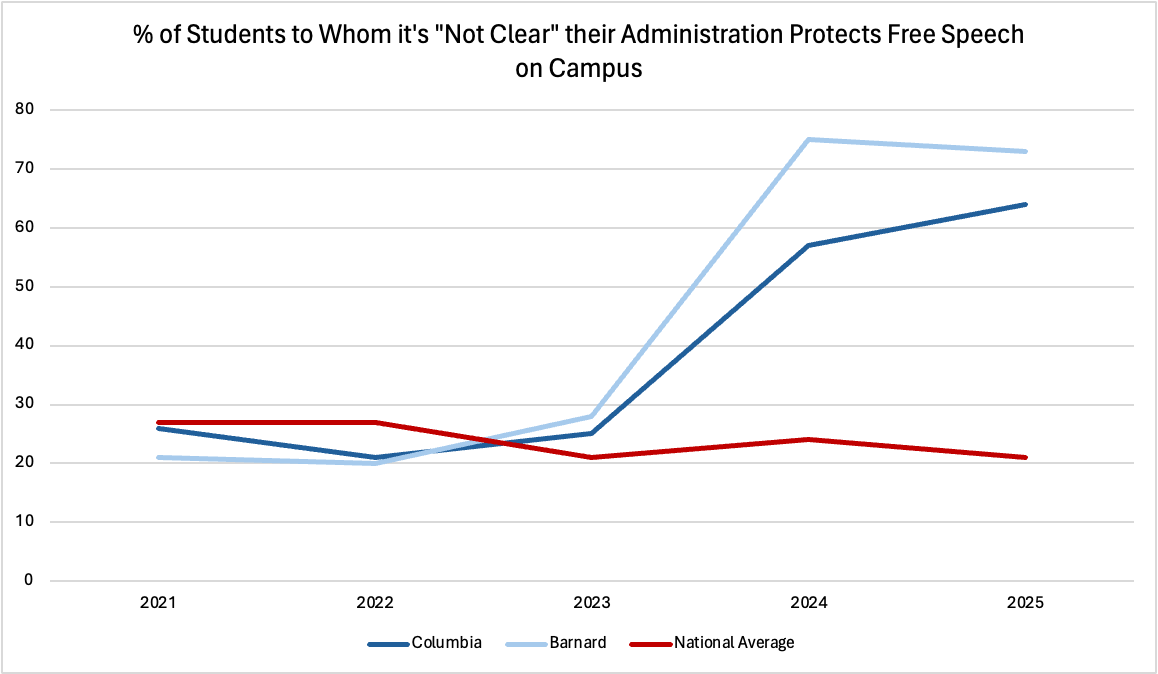

In the survey, students were asked to evaluate their administration’s support for free speech. According to Stevens, Columbia students’ evaluations were some of the worst of any ranked college. As one could guess, only Barnard was considered worse.

In fact, Barnard’s ranking was the lowest ever recorded for any school. Cited incidents include that of Georgia Dillane, a WKCR reporter whose “press freedoms” were threatened by Barnard for her alleged participation in a March 2025 protest she never actually attended.

When asked, “How clear is it to you that your college administration protects free speech on campus?” 73 percent responded that it was “not clear,” with an additional 24 percent saying it was only “somewhat clear.”

Do these results say more about students or the administration?

In these pages, I have previously criticized students’ attitudes toward controversial speakers and self-censorship as reasons why Columbia finished second-to-last in last year’s rankings. The data this year, however, suggests that students here in Morningside Heights aren’t necessarily less tolerant than the average college student.

Of the students surveyed around the nation, 15 percent view violence as “always” or “sometimes” acceptable to limit speech; in comparison, 12 percent of Columbia and 13 percent of Barnard students share the same view, which is also lower than the responses from five of the top 10-ranked colleges. The same applies to the percentage of students here who believe in “blocking others” from attending campus events.

That said, Columbia’s public spotlight might mislead some outside our community into thinking that the average student here is disrupting a ‘History of Modern Zionism’ class or occupying libraries.

“Occupying a building, not cool, not legal, that crosses a line,” Stevens says, but the onus of an “F” free speech grade? “That’s far more on the administration than what the students have done.”

One can sense that administrators are feeling the pressure from the rankings. A few weeks after they were released, Columbia’s “President’s Advisory Committee on Institutional Voice” decided that, after over a year of deliberation, the University should “exercise restraint” on speaking about issues that “do not directly threaten Columbia’s paramount values.” Meanwhile, Barnard Dean Laura Rosenbury argued in a New York Times op-ed last month that universities need to “reconfirm our commitment to nonviolent forms of disagreement.”

Stevens and I commend Rosenbury’s acknowledgment of how important free speech is, yet while this would normally be cause for hope, I was also optimistic last year after Barnard committed to institutional neutrality just days after last year’s rankings.

Indeed, institutional neutrality presents a great opportunity, as it confines administrators’ role to publicly defending free and open discourse, rather than picking sides. Columbia’s positions on issues in the past have left no shortage of controversy, from then-President Michael Sovern criticizing the “stupidity” of Apartheid South Africa protesters, to Columbia SJP’s opposition to Barnard Dean Leslie Grinage publicly labeling October 7 an act of “terrorism.”

I concede that institutional neutrality seems like a bad idea if the University completely agrees with you on every single issue it feels the need to comment on. But for how many people, if any at all, is this the case?

Even if certain topics do warrant comment, the administration should be in no place to choose sides. FIRE’s rankings have clearly demonstrated just how unpopular these administrators are to Columbia and Barnard students. Why should these same administrators now be granted the ability to speak biasedly on behalf of their respective institutions?

Given that students are still uncertain about institutional neutrality, administrators must do a better job not only standing up for free speech, but also demonstrating their commitment to it. More specifically, they need to clarify how policies like institutional neutrality will both address student concerns and our University’s problems.

Administrative committees and fresh-from-source op-eds, while they might sound nice, reflect the bare minimum. Columbia and Barnard’s commitment to these principles should be clearly communicated to the student body, whether it be through hosting town halls, sending short and straight-to-the-point University emails, engaging with student and community leaders, and slashing the red tape for clubs and organizations hosting speaker events.

While Stevens agrees that “students can really put pressure on their administration to do the right thing,” the ball is largely in the administrators’ court.

As mentioned earlier, these rankings have their limits, and survey data can only convey so much about the problem. However, as students, we’ve witnessed how a lack of dialogue can spark division, and we owe it to future generations of students to regain our community’s intellectual health. The journey out of rock bottom will be a long one, but as far as rankings go, the only way for Columbia and Barnard to go is up.

Mr. Baum is a junior in the joint degree program between the Jewish Theological Seminary and the School of General Studies. He is a senior editor for Sundial.

The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Sundial editorial board as a whole or any other members of the staff.