Inside the Ivy League’s Conservative Coachella

I arrived at the David Network annual conference with a certain understanding of American conservatives. I left with something completely unexpected.

“Please indicate your gender: I) Male II) Female.”

Why was reading this disorienting to me?

Even before arriving at the David Network’s annual conference in Washington, D.C. in late January, I was met with the cultural reverberations of immersing myself within the Ivy League’s most expansive network of conservative students. To my surprise, the form to sign up for the conference, which was all-expenses-paid, already led me outside my intellectual comfort zone—male, and female. Two, just two, genders.

I wasn’t focused on whether this made me angry, or if I agreed. Rather, this was the first of a long set of observations during my weekend at the David Network that made me feel the gravity of the dissonance between American liberals and conservatives.

There are few opportunities to observe the world of uninterrupted conservatism from within, and I knew I would regret not taking this opportunity. So off to D.C. I went.

The Journey to DC

Waiting for the bus outside Columbia’s Northwest Corner building with other duffel bag-bearing conference goers, I felt oddly pensive. As I made small talk with the bus coordinator and others, I remember thinking to myself: I would never have known if these people were conservative or not just by looking at them. What’s more, I realized that everyone I spoke to assumed that I was conservative myself.

Almost immediately, my assumptions about the conservative world were challenged. En route to D.C., we made a stop for a bathroom break at the Biden Welcome Center just outside of Newark, Delaware. For some reason, I assumed our group would find somewhere more conservative to stop and stretch our legs, avoiding the Biden Welcome Center with disdain.

As we arrived at our hotel and got dressed in token conservative business casual attire (suit jacket, dress shirt, no tie, with the first button undone), I caught myself perceiving all of my surroundings through an abnormally political lens. As I looked around the hotel room, I remember thinking to myself that everything felt so—for lack of a better word—conservative. Wow. Look at all of these conservative pillows. Conservative television. Conservative Dove bar soap wrapped in foggy plastic. Conservative mini Keurig.

At the welcome dinner buffet, the lens intensified: conservative mashed potatoes, conservative fried fish, conservative salad with plum tomatoes cut into awkward thirds, conservative churros (don’t ask).

I anxiously found a table and began eating my conservative buffet selections. Oddly, at that moment, I felt fearful that I’d be outed at any moment as a New Yorker, a Harris voter, or a gay Manhattanite with a snake earring on his right earlobe (I insisted to anyone who inquired that it meant “don’t tread on me”). As I looked up from biting into my liberally salted potatoes, I became acquainted with a kind conservative Ivy League couple at my table—high school sweethearts from Cornell and Yale in a long distance relationship.

While the couple was undoubtedly pleasant, I felt the writing on the wall. “They’re gonna know I’m not conservative,” I thought to myself. After asking them what being a conservative was like at their respective universities, they returned the favor:

“What’s it like being a conservative at Columbia, Alex?”

What happened next prompted a chain of events I could never have predicted for myself.

“It’s alright, we have a really close-knit community. Columbia is pretty liberal, but it’s just really good to have each other,” I said.

With each new person I met that night, my story developed further. As I leaned further into this instinct to act conservative (which I admit was morally grey), I noticed that it allowed me to better understand why so many of my new conservative friends think the way they do.

The Conference

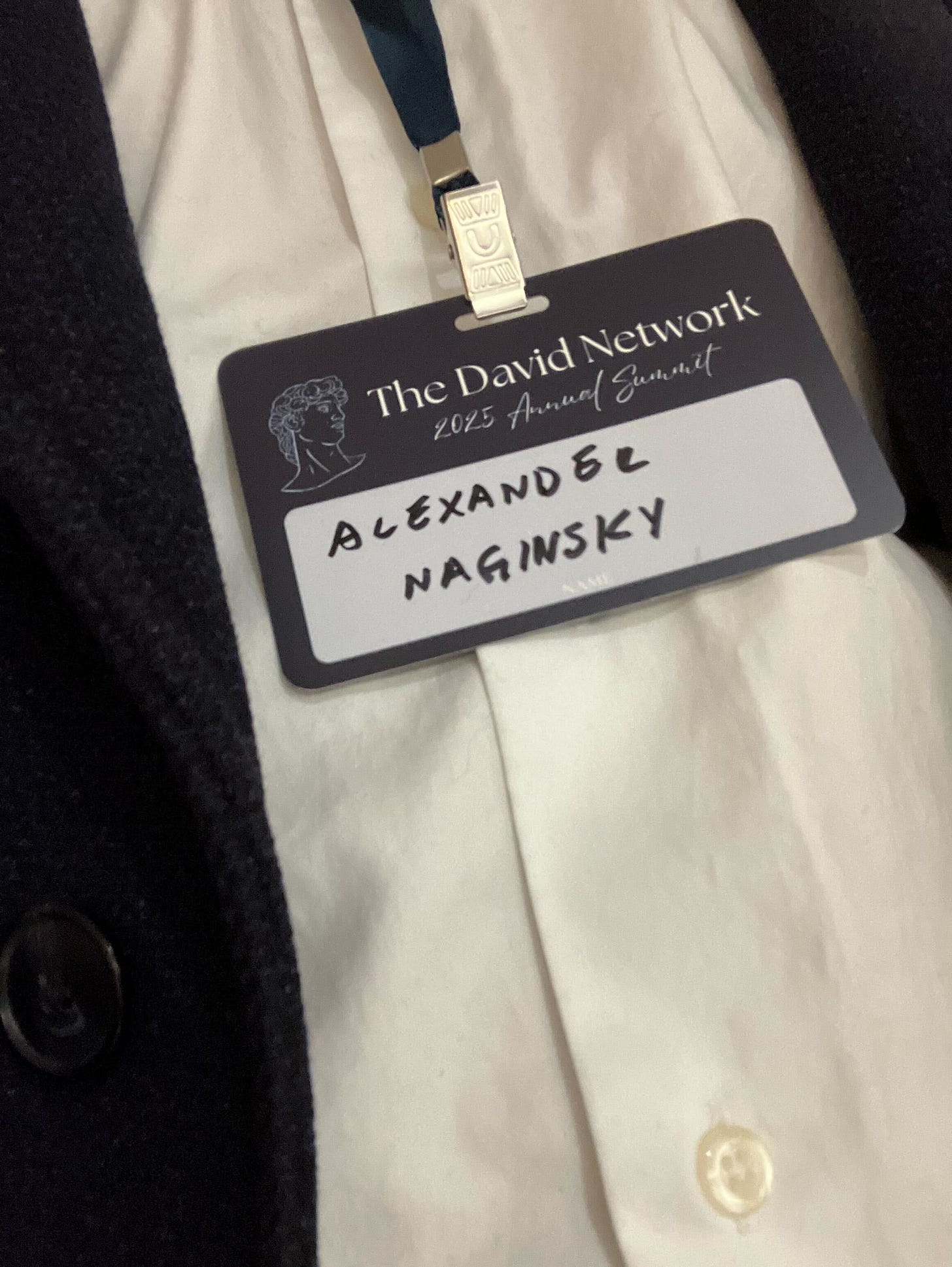

At the check-in table for the conference the next morning, we were given name tags and a simple task: Write your name in Sharpie. Something about writing “Alex Nagin” felt wrong to me. Sure, that’s my name, but once again my paranoia prevailed—for some reason I was convinced that none of my peers at the conference could have possibly believed that “Alex Nagin” was a conservative. So I workshopped for a moment to settle my anxieties.

“Alexander Naginsky,” my name tag read. Alexander, my full name which I’m rarely referred to by, and Naginsky, the family name of my Slavic ancestors before it was Americanized to simply “Nagin.”

Shaking hands with conference-goers at the breakfast table I was assigned to, I did my best to project confidence as I acquainted myself with the endless new faces surrounding me. “Alexander Naginsky, a pleasure.” Despite my commitment to my story, I found myself forgetting my alter-ego.

Even so, when I was engaging with the other students at my table and throughout the day, I found myself not only finding common ground but agreeing on a surprising number of topics.

“Liberal hypocrisy has fueled inequality in America’s largest cities.” I agreed.

“There’s some moral legitimacy to both sides of the abortion debate.” I agreed.

“Leftist activists are pretty uninterested in dialogue.” I agreed (although I despise the term “leftist”).

Was I a conservative?

The truth is, attending the David Network conference reminded me that I—like most people in this country—am not interested in publicly siding with any singular ideology, party, label, or identity that allows others to make assumptions about me without conversation.

Many of the students I met defined themselves as “right-leaning” to me during the conference. I’m no linguist, but there’s something to be said about “leaning” a certain way. When you lean, you’re off balance. You can bring your politics back to center just as easily as you can bend your torso in one direction or the other.

After Stephanie Gray, a pro-life speaker, delivered an impassioned keynote address, I chatted with some students outside the theater. Without me even bringing it up, the group I was with discussed how they thought Gray’s speech was too extreme. They took particular issue with her argument that rape victims should carry their pregnancies to term because the fetus did nothing to “deserve the death penalty.” At this moment, it seemed that these students leaned ever so slightly towards the center of the political spectrum.

Conservative Cosplay

Throughout the David Network, where high-profile conservative celebrity appearances were all but rare, I sought to gain the fullest possible understanding of the modern conservative movement. I had to go all in on my new conservative identity. So far, in fact, that I ended up snapping a picture at the very end of the conference with none other than Jeff Sessions, Donald Trump’s first Attorney General. Yet this only occurred because of my effort to perfect my conservative persona over the course of the weekend.

Indeed, the night before the main day of the conference, I couldn’t help but feel like I was cast in “Younger,” a cheesy MTV sitcom where Sutton Foster plays a 40-year-old mother posing as a 26-year-old trying to work her way up New York’s publishing industry. She gets a boyfriend who thinks she’s 26, makes friends “her age,” and almost outs herself in each episode. Throughout the show, Foster’s character’s secret slowly unravels: Her hipster tattoo artist boyfriend discovers her true age, and she continually makes references to growing up in the 80s on accident in front of people who don’t know her secret.

During the conference, there were several times when I “slipped up” like Foster’s character, almost exposing myself by instinctively reacting to the conservative mentalities of those around me. This wasn’t because I vehemently disagreed with the other Ivy Leaguers I met—rather, I had to tone down my reactions to hearing about upbringings and lifestyles that my true left-leaning self was fascinated by. As the day progressed, I had to condition myself to intellectually and spiritually blend in with my surroundings.

The Debate

Within the first few hours of arriving in D.C., I learned that vernacular was a key way many in conservative circles signal their anti-progressivism.

On the first night of the conference, there was a chamber-style debate in a large, old, hardwood-paneled (but still ugly) room a few floors above where the welcome reception was held. The chairs were configured into a massive circle. Think AA times ten, or a ginormous intervention for that one friend.

One by one, debaters stood up and entered the space in the middle of the room. With the passion and volume of a priest preaching at his holiest moment, they argued the resolution, “Long Live Democracy.”

One of the debaters suggested in his speech that only Americans with children should be able to vote. In a rebuttal, another debater inquired about where his opponent, a man of color, was “really from.”

Now, I won’t be dramatic about this—it was clearly an edgy and impersonal joke. The room had a very innocent laugh and no one took it very seriously—except perhaps for the debater who this comment was leveled against. He let out a slight chuckle, but before that I saw with clarity what I can only describe as an uncomfortable, pensive smile on his face. The discomfort the debater felt was not rooted in some sort of secret left-leaning belief—it just seemed unavoidable.

Another notable moment from the debate that garnered room-wide laughter was one debater’s assertion that “democracy is gay.” This was, presumably, his punchy and attention-grabbing way of pointing out flaws in the democratic system.

At the moment, I did not think too deeply аbout either of these statements. I wasn’t offended. I wasn’t angry. I wasn’t upset. I just noticed.

In liberal spaces, these linguistic nods mocking “wokeism” are seen as irrefutably problematic and emblematic of oppression, disrespect, and prejudice. For the first time, I realized why this doesn’t hold true in conservative spaces. After chatting around the event, I can confidently say that no one in that room had any personal motivations to insult the LGBT community. After all, this part of the debate wasn’t about queer identity. Instead, these words exemplified a variety of right-wing “anti-woke” virtue signaling. Using this conventionally problematic language during the debate was instead a way for these conservatives to tease liberal ideology.

Don’t get me wrong. As a gay man, I can tell you that calling democracy “gay” probably isn’t kosher. Based on the subtext of this strange situation, however, here’s what I can say: Because of cancel culture and sanitized mainstream cultural discourse, calling something “gay” will prompt a reaction instead of a conversation. So, the language was a way for this debater, perhaps without him realizing it, to say to his fellow conservatives: I am one of you. I don’t believe in “wokeism.” We aren’t like them.

Aside from this epiphany, I was tempted to contribute a point of information to the debate that by this debater’s metrics, his unremarkable height or hairline could also be considered gay.

An Unexpected Reunion

While waiting to enter the auditorium on the main day of the conference, I locked eyes with a face that I hadn’t seen in three years.

My friend from high school, who I did not know was conservative, came up to me and said hello. When he looked at me, he had one of the most confused yet intrigued smiles I’ve ever seen in my life—likely because in high school, I was openly hyper-liberal and unwilling to budge on any of my beliefs.

Back then, I would reprimand my family for neglecting to recycle. I hung up a copy of the Communist Manifesto in my room. I accused my dad of being a token “white man” for telling the family Border Terrier to stop barking. I wasn’t the easiest to be around.

After reconnecting and telling my friend I was writing an article about the David Network, he immediately offered to comment.

“I’m really impressed by how competent this new young conservative elite at the David Network seems to be,” he remarked.

“And this is kind of a bad thing, because it implies that there’s not that much competence in the rest of society. At [my university], there are some people who impress me enormously, and a lot of them are gathered here that I didn’t even know were conservative.”

Why hadn't I noticed this disconnect between this “new young conservative elite” and the modern Republican Party? The answer was obvious, but it took the effort of immersing myself within the conservative—not Republican—world to realize it.

Young conservatives—and more broadly, students who hold any beliefs that deviate from the ideological majority—aren’t propaganda-inspired agents of the Trump Republican party (I only spotted one MAGA hat among the hundreds of conference goers). Especially in the Ivy League, they are open-minded, independent, and not afraid to point out where their own beliefs differ from the modern Republican Party at large.

Beyond this, there have been countless times in the past when I’ve heard right-leaning students referred to as “stupid,” “idiotic,” and “insane” for their beliefs. As I learned at the David Network, many of my new conservative friends aren’t just academically smart—they’ve thought very deeply about their beliefs and why they hold them. The prejudicial thoughtlessness the masses assume they exude does not exist.

In my view, the problem with the current political discourse seems to be the fact that many liberal Ivy Leaguers judge others for holding different beliefs without interrogating their own. And I say this referring fully to myself.

The Final Word

Reflecting upon my weekend at the David Network, I can’t help but remember my mindset before deciding to go. Is this even going to be worth it? Should I even go?

There proved to be great, unironic value in my conservative cosplay that I would have never had access to without the David Network. In many ways, by attending this conference, the David Network flipped the script on the typical conservative experience at Columbia. Each day, the conservatives of the Ivy League walk around their campuses in the ideological minority, having to pick and choose where and when their beliefs will be accepted and tolerated. I am in no way trying to insinuate that conservative Ivy Leaguers are oppressed (it would be beyond ironic to assume so). That said, “becoming” ideologically one with a group of people my younger self would have perceived as enemies, I was able to put my own beliefs and values to the test.

Certain personal beliefs of mine were strongly reinforced by my weekend at the David Network: The right’s fundamental misunderstanding of transgender identity. Abortion rights. Firearm regulations. Yet others I was forced to grapple with meaningfully for the first time—fiscal policy, the free market, and national defense. I didn’t necessarily change my beliefs on these subjects, but I reckoned with the fact that when presented with rational conservative arguments on them, I simply did not have an intellectual foundation to meaningfully engage in debate. Why? Because for so long, my liberal bubble—both from high school and college—conditioned me to know only what to believe, not why to believe it.

I won’t lie. The David Network conference was not full of rainbows and butterflies. Many of the speakers and presenters were focused on the idea that conservatives are in an ideological war against the “commie” left, to quote Joe Lonsdale, the co-founder of software company Palantir and one of the keynote speakers.

One of the panels I attended, “The Assault on the American Family,” revealed this dynamic to me as well. The speakers on the panel consistently used phrases like “they want to” or ”they’re trying to.” But at one point, it became unclear who this “they” was. Democrats? Liberals at large? Transgender rights activists? Judith Butler? I honestly have no clue. What I could tell, however, was that even though Trump is back in power, the David Network as an organization feels that America still faces pervasive cultural and institutional threats.

Whether we like it or not, the left and right, liberals and conservatives, and Democrats and Republicans will be fighting this “war” for the majority of our lifetimes. For the young people on both sides, we should ask: how should we get involved in a conflict so ideologically bloody and cruel when all we want to do is look the other way? How do we reason with people we perceive to be immoral and heartless? How can we possibly begin to have productive conversations when all that our politics teaches us is that we must win or lose, cheat or be cheated, and fight or concede?

The more we become a part of each other’s worlds, the more we create possibilities of finding common ground. Under the guise of Alexander Naginsky, I was able to create meaningful dialogue with people who had essentially no idea they were talking to someone who voted for Kamala Harris in the last election. I chose not to reveal this fact—hence the birth of “Alexander Naginsky”—because if I did, my peers would look at me differently, as an agent of the liberal agenda. But the blanket “liberal agenda” is not why I voted for Harris. I voted for her because I had to weigh my personal values, in all of their complexities, with the two candidates the parties nominated. For me, there were just some things I could not sacrifice by voting red.

But my new friends voted for Trump using the same logic. Many of them were first-generation Americans and felt strongly about border security. Their parents owned businesses and wanted to vote for a change candidate who might deal with inflation differently. And I don’t judge them for that because that’s their life experience, not their “prejudice” or “hate.” It’s just a product of the complex mosaic of beliefs that inform all of our worldviews. The ideological shackles of the two-party system need not penetrate every conversation we try to have with one another.

It is this revelation that I left D.C. thinking about the most. The Ivy League—both the emerging conservative and liberal elite—is teeming with young people who will one day walk the halls of power. When they reach those halls, they should remember that they have the unique potential to turn the tide on the ugly politics that we suffer from today.

Mr. Nagin is a junior in the Dual BA program with Trinity College Dublin majoring in political science. He is the deputy editor of Sundial.

thoroughly enjoyed this conservative read alex, well done !