The Story of Columbia’s Architecture Through the Decades

Lessons we can Learn-er from Columbia’s little-known architectural history.

Uris. Mudd. Lerner. Like any university, Columbia has no shortage of polarizing architecture. Chances are, you or someone you know has walked past one of these buildings and asked: “Why can’t they look like the rest of campus? Why don’t they resemble the elegance and ornamentation of the older buildings here in Morningside Heights?”

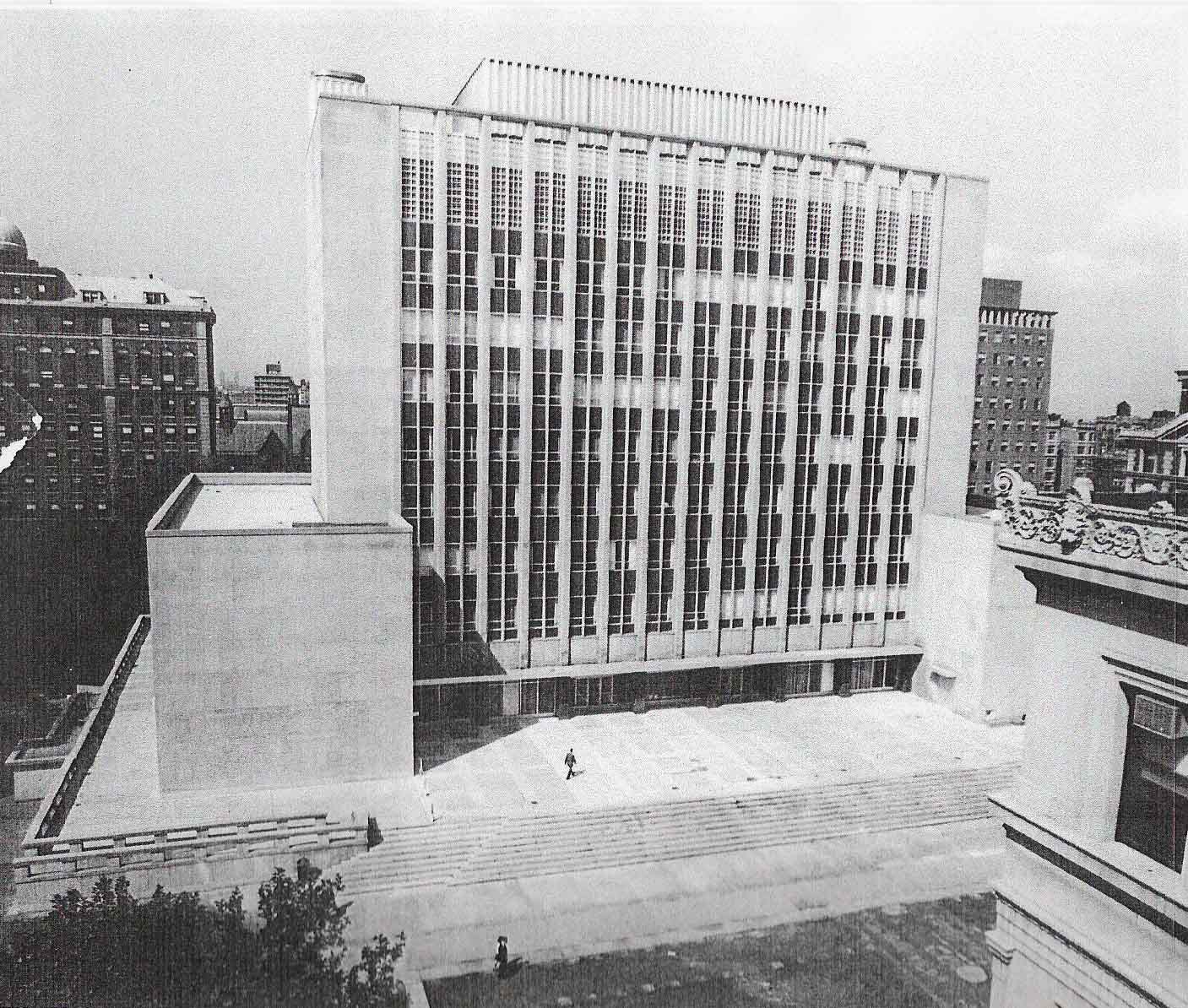

As it turns out, complaining about architecture has been a Columbia tradition. When Uris Hall was unveiled in 1964, it was protested by architecture students with signs that read “No more Mudds,” while an architecture professor gave a radio interview on the structure that was allegedly so scathing it was confiscated by campus security before it could air. If you think the building is ugly now, consider what Uris used to look like before they retrofitted the current facade in the 1980s.

Similarly, New York architect Susanna Sirefman likened the glass of Lerner Hall to a “1980’s dentist office,” and author David Garrard Lowe wrote that it gives “the impression of an edifice on the verge of a nervous breakdown.” One local resident in a letter to the Architectural Record complained:

There is absolutely nothing in its design that would look out-of-place in a fancy strip-mall in New Jersey… The entrance? I say, Bed, Bath & Beyond, route 85 in Mahwah. The roof? Home Depot, East Rutherford. The east wall? Maybe a welfare office in downtown Newark.

As a New Jersey native, I’m not sure whether to be offended or pleased by this comparison. Nonetheless, all this negativity brings us back to that same question: did architects simply lose interest in the original style of Columbia’s buildings, or is there something we’re missing with these newer additions to campus? To tell the story of Columbia’s architectural evolution over the decades, I spoke with none other than the architect of Lerner Hall, and chair of Columbia’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation, Bernard Tschumi.

To Tschumi, good architecture is about being “sensitive without being a pastiche,” he told Sundial. By that, he means that buildings ought to “allow a dialogue” with the surrounding space, not copy and paste from neighboring buildings, but provide a fresh, modern update instead. While the 81-year-old architect has built everything from Athens’ Acropolis Museum to the Paris Zoo to a Lower East Side high rise, he sees Columbia’s campus as the gold standard of this approach.

The Morningside Heights campus has been defined by the Beaux-Arts architectural style that was popular at the turn of the 20th century. Built by the firm McKim, Mead, & White, it marked a significant and intentional shift from the gothic architecture of other universities, and symbolized Columbia’s relationship with a persistently modern and urban area (even though the neighborhood didn’t look quite so urban when the campus was first built).

Fascinatingly, the green-roofed halls of Columbia’s campus are intentionally built not to look identical. The next time you walk down Broadway, notice the subtle differences in the brickwork, patterns, and ornamentation of each building. In architecture, this is the idea of “correlation,” which Tschumi indirectly describes as striking “intentional coherence” between elements while reserving “some differences.”

Needless to say, structures like the Northwest Corner Building (NoCo) and the Law School (Jerome Greene Hall) hold more than “some differences” from the surrounding campus. They seem to be standalone constructions that break the “correlation” that McKim and co. envisioned. I wanted to ask, “Where did we go wrong?” but Tschumi believes that we never lost sight of that idea. It’s just that instead of striving for an aesthetic correlation, these newer buildings have instead followed an ideological correlation with the rest of campus.

Just as the original Beaux-Arts style of Columbia served as a modern alternative to the collegiate gothic norm, buildings such as NoCo and the Law School were also built as modern alternatives to traditional university architecture. In other words, they were built in the same spirit of modernity and innovation that shaped Columbia’s campus in the first place.

“I think every more recent building was still being very respectful of the original master plan,” Tschumi said, even finding NoCo “to be one of the buildings I like best on campus.”

Indeed, one thing that virtually every building on campus has in common is that they’re built in the style that was popular for the time. The original campus was built in the Beaux-Arts style of the early 1900s; Uris, the Law School, and the International Affairs building in the brutalist style popular in the 60s and 70s; the Schapiro Center and the William and June Warren Hall in the postmodernist style of the 80s and 90s. And NoCo and Lerner Hall in the contemporary, high-tech style of the 21st century.

Tschumi enjoys seeing students fashion new uses out of his architecture, such as with graduation

Tschumi himself can attest to the “interesting predicament” that Lerner Hall found itself in. “We were very consciously trying to jump into the 21st century,” he said, while preserving “the unity of the facades on Broadway. It was really necessary to keep it, but not to be literally copying the details of the time.”

How do you make the jump? To the student center architect, that involved reimagining a favorite campus spot—the steps of Low Library—and creating a “contemporary, indoor equivalent,” one that has “a different use, a different program, with transparency looking towards campus from that location.” At the same time, the building used “the same materials, breaks, and even the same pink granite” that comes from the same quarry in Connecticut as those used by the more traditional buildings on campus.

Of course, this doesn’t necessarily justify all that we consider “ugly” on campus. Rather, it reminds us that at one point, the brutalist style of Uris was just as fashionable as the modern look of the Manhattanville campus is now. Columbia’s architecture has long followed a unifying theme: adhering to the prevailing style of the era. Thus, most buildings reflect the architectural trends of their time. But when they don’t, the result can feel jarring, or even inauthentic.

Shortly after designing Lerner Hall, Tschumi was in charge of building Florida International University’s new architecture school. When he visited the campus, he recounted that it “had a lot of very nice buildings from the 1950s, but it then suddenly decided to build in this large 18th century Spanish style.”

“I thought, ‘Well, it looks a little fake.’ So it’s about fitting the pattern of campus while trying to innovate and introduce something new,” he said.

And indeed, while some more recent buildings like NoCo and International Affairs only seem to fixate on an ideological correlation with the rest of Columbia, other recent buildings like Lerner, Uris, and the Schapiro Center model hold some important architectural similarities. The latter two buildings align with the vertical axis of Low and Butler libraries, and they match their gray exteriors, slender columns, and vertical elements through their own respective styles.

Again, this isn’t to defend all of Columbia’s modern campus additions. I still consider Uris to be an eyesore, and I frequently get lost on my way to the bathroom in Lerner. But after talking with Tschumi, I was able to understand why these buildings look the way they do; they were built in the same innovative, modern spirit that all Columbia buildings found themselves in at one point.

I still had one lingering question for Tschumi: if these buildings of various styles, colors, and designs can all be considered consistent with Columbia’s “master plan,” then what would be an example of something that violates this plan?

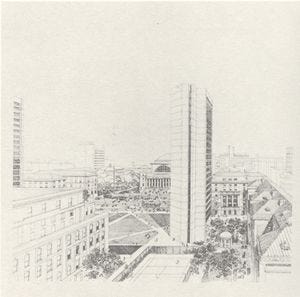

He pointed me to an instance in 1968 when the architect I.M. Pei proposed building two 20-story glass skyscrapers on both sides of the Butler lawns that would serve as student dorms. The proposal also suggested hollowing out the Butler lawns themselves and turning the space into a student center.

While McKim, Mead, and White envisioned a modern campus built to grow along with New York City, I’m sure even they wouldn’t have been pleased seeing those towers erected right in front of Butler. Columbia has its ugly buildings, but in one form or another, they hold some ideas in common and stay true to the ethos of Columbia. While that shouldn’t erase our tradition of beating up on the buildings we don’t like, we can at least have a bit more appreciation for the story behind them.

Mr. Baum is a sophomore in the dual degree program between Jewish Theological Seminary and the School of General Studies. He is a staff editor for Sundial.

Good article. I remember the first time I saw the new modernist giant looming behind the curving dome. Someone called it "Jayne Mansfield at the Board of Directors meeting."

Wonderful! Really enjoyed