The Soul of the Core is Alive and Well at the Morningside Institute

Reading Peter Thiel and Roger Scruton at the Institute, I learned that education—at its best—is a companion for life.

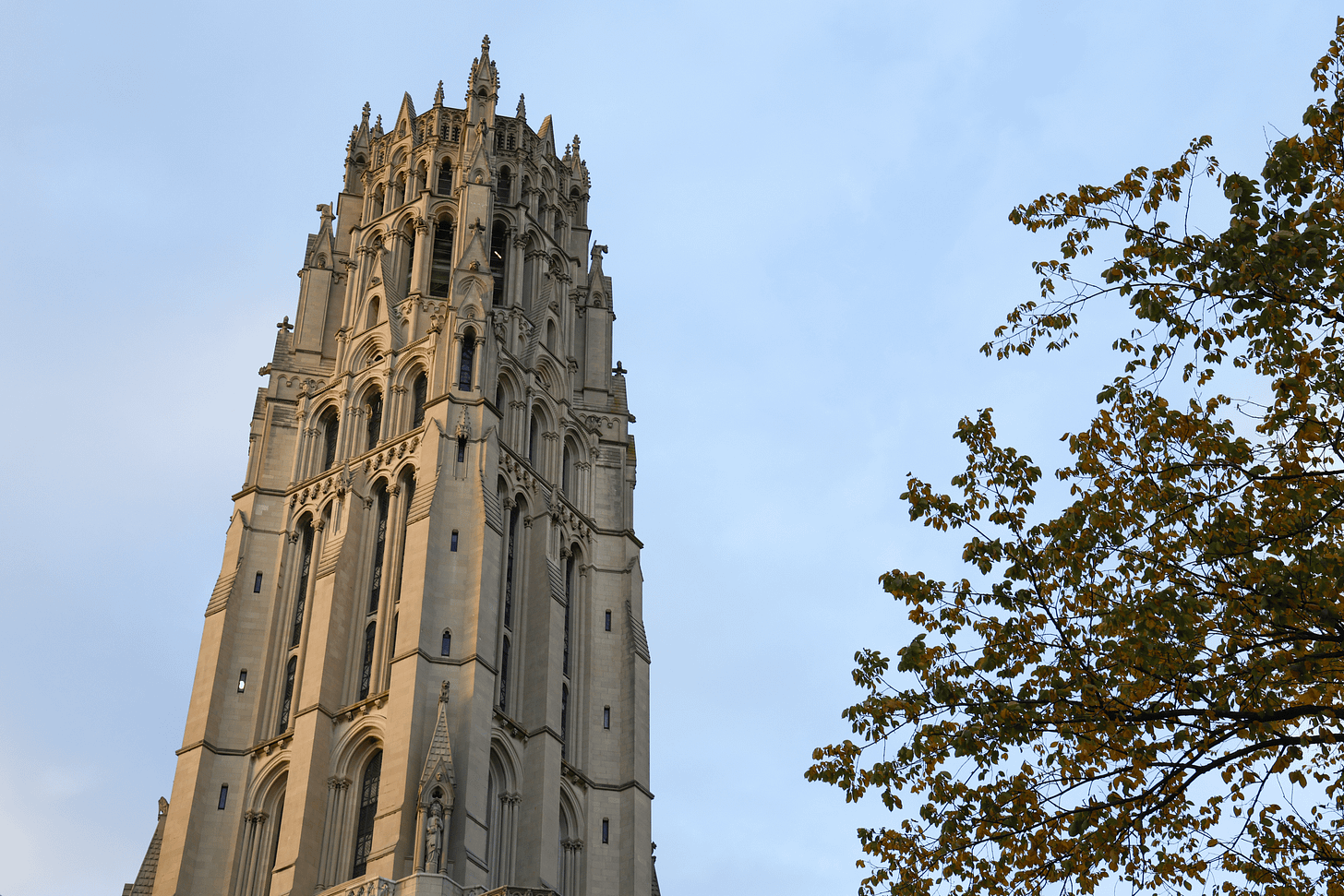

Nestled away in the heart of Morningside Heights’ Riverside Church lies a space that feels at once both ancient and new. It isn’t a sanctuary in the religious sense, though the vaulted ceilings and soft echo of conversation might suggest as much. Rather, it is an intellectual refuge: the Morningside Institute.

Founded in 2017 as an independent nonprofit organization, the Institute has quietly grown into one of New York’s most compelling communities devoted to the liberal arts. Though not directly affiliated with the University, it hosts Columbia professors and features topics relevant to Columbia, such as the Core Curriculum, in its free programming. Within its literature-lined rooms, people at all stages of their educational journeys—college students, scholars, erudite New Yorkers—gather for reading groups, dinner discussions, and cultural outings that traverse the broad terrain of the humanities.

To enter this space is to encounter a vision of education that feels increasingly rare. The Morningside Institute provides no credentials, no grades, and no recognition that can be spun to support professional ambition. Yet, in the absence of such characteristics, it seems that it is where education’s true purpose is reclaimed. As Nathaniel Peters, the director of the Institute, told me, the Institute’s mission is to “bring education back to its core, to have a place where you could pursue important ideas and get to the heart of questions that we all have as human beings.”

A Haven For Thought

I first stumbled upon the Institute in a previous edition of Sundial, where guest writer Nathan Darmon, in his article, “The Intellectual Dark Web of Morningside Heights,” briefly describes the Morningside Institute as a space bringing the Core Curriculum to life outside the classroom. Having grown to love the Core’s spirit but often wishing to linger on its ideas, I was immediately drawn to the Institute. When I attended my first seminar, I found exactly what I had been looking for: a place where literature, philosophy, and the humanities were explored with the kind of patience and reverence that real understanding requires.

The more I experience the Institute, the more I believe that to be true.

Its gatherings tend to be intimate: around a wooden table or in a small circle, students sit beside professors, plates pushed aside, readings opened, with conversation flowing freely. There is no moderator policing comments, nor a sense of competition to perform intelligence for the sake of a grade. It is purely a setting designed to allow current and lifelong students an opportunity to engage with thinkers they rarely come across in a classroom.

Recent seminars have covered everything from the philosophy of the “Tech Right” to what the “End of History” looks like, to the perspective of a “Beginner’s Mind.” While each discussion broaches a separate, seemingly abstract topic, they all carry strands of humanistic thought. However, having enduring themes does not indicate lasting agreement; on the contrary, vigorous debate thrives in this environment.

In a seminar on Peter Thiel’s “Nihilism Is Not Enough,” I witnessed exchanges over Thiel’s philosophical stances, the form of his proposed Antichrist, and our reason for existence. One attendee interpreted Thiel’s transhumanist outlook and depiction of societal stagnation as aligning with the accelerationist view. Another disagreed, arguing that Thiel’s emphasis on the “katechon,” a biblical reference to “a power keeping the Apocalypse at bay,” stands in opposition to the accelerationist embrace of systemic collapse.

Similarly, in a series of lunch discussions on Roger Scruton’s The Soul Of The World, opposing opinions on scientific reductionism and the existence of the “sacred” went to war. Most dismissed evolutionary psychology as an adequate explanation for the human experience—art, music, religion, beauty. A few, either out of personal belief or by playing devil’s advocate, argued that functional adaptations and the rise of artificial intelligence could explain away what Scruton describes as the “transcendental” dimension unique to human beings.

These moments stayed with me. As a staunch atheist, I had long believed that reason and science could account for our physical sensations and psychological tendencies. Yet, the Scruton conversations pressed me to ask whether it was true that everything meaningful in life could be measured, categorized, or proved in empirical terms. Similarly, I entered the Thiel seminar skeptical of his self-serving corporate theology. Yet, I found myself acknowledging his arguments about societal stagnation and the idea that our civilization’s malaise stems from the absence of an ultimate purpose.

Over each seminar, I also began to notice subtle connections between the Institute’s choice of readings and those in Literature Humanities. Of course, they occupy very different worlds. One does not read Thiel the way one reads Homer. Yet, beneath the surface lies something familiar: a shared attempt to grasp what it means to live meaningfully in uncertain times. Whether through ancient myth or modern philosophy, both sets of texts pressed us to face the same universal human anxieties in different forms.

That parallel became most vivid in the way each space handled disagreement. While disagreement is common in any Columbia seminar, its texture at the Institute felt distinct. Literature Humanities moves swiftly through monumental works, spending only a couple of classes on Homer’s Iliad or Vergil’s Aeneid, leaving much to be desired. Discussions stay shallow and are often cut short due to time constraints. The Institute, however, slowed the process, devoting a two-hour session to dissecting a few passages and arguments. Only in this slower environment was I able to truly interact with readings like Scruton’s The Soul of the World as a dialogue rather than an obligation.

I have come to see this as a different kind of liberal arts education than the one Columbia provides for its students. Thus far, my experience in Literature Humanities has been one of breadth, passage analyses, and intermittent essays and tests. Though I am certainly proficient in recognizing literary allusions and their origins, I still feel as if I am missing something critical that I came to Columbia for. For me, truly experiencing the liberal arts means dwelling within ideas, having my convictions tested, and asking questions without the expectation of a definitive answer or grade for my performance.

The Meaning of the Liberal Arts

The liberal arts have long been misunderstood as a luxury, a pursuit for only those with leisure or privilege. Yet, the term “liberal” originally referred not to politics or economics, but to freedom. To study the liberal arts, then, is to seek freedom from ignorance, from shallowness, from the tyranny of unexamined assumptions. It is to foster the inner liberty that allows one to see the world as more than a marketplace or résumé.

This vision stands in stark contrast to the utilitarian ethos that dominates much of higher education. What I have found from my short time here is that students are told, explicitly or implicitly, that the purpose of university is to gain employable skills, to position themselves for success in a competitive economy, and to network with fellow students for future connections. As a result, students opt out of humanities classes or, when required, utilize online summaries and AI services to avoid “wasting time.” Accordingly, universities respond to lower enrollment in the humanities by either reducing funding or cutting entire programs.

Perhaps it is naive to expect people and institutions to embrace such a romanticized view of education in our era of commercialization. However, if education were reduced purely to molding students into the perfect worker, it would be nothing more than occupational indoctrination. As Peters puts it, education should not be something that is “purely instrumental, but something that you can enjoy and rejoice over for its own sake.”

Education, at its core, is about forming a person, and the liberal arts are its tools. When one ventures into all it encompasses—language, literature, philosophy, anything that defines our humanity—it becomes possible to see beyond the busyness burdening our minds at all times. To linger on these topics, to ignore the need to constantly be in motion, to discover who we truly are—that is what the Morningside model offers.

Why the Morningside Model Matters

The Morningside Institute’s greatest contribution to students may be its emphasis that the “subject matter of the liberal arts is life.” To study them is to affirm that truth, beauty, and goodness are real, and that they deserve our attention. It acknowledges that life’s most important questions—What is justice? What is happiness? What is worth loving?—cannot be answered by algorithms or economic models alone. Similarly, it cannot be answered in a fast-paced classroom where students are, to some extent, simply fulfilling a requirement to pass a class.

Finding one’s own way to live the liberal arts has to happen outside of the classroom. This is where Morningside fits in for Columbia students. Morningside acts as a tuner for the human soul, inviting attendees to approach learning as a companion for life, as a mirror in which to see ourselves more clearly.

Perhaps that is why its mission feels so urgent to me. Amid the noise of achievement and modern metrics of success that have infected Columbia students’ goals, the Institute recalls something older and truer: that the life of the mind, pursued freely and with sincerity, is one of the highest forms of joy. It revives the endless curiosity I once held as a child, before it was dulled by transcripts and applications. And in a time when many have forgotten what education is for (at times, even myself), that joy might be the most radical form of all.

I look forward to spending the next three and a half years cultivating this spirit at the Institute. So, to those who also believe that education is more than just a means to an end, I say this: find your place. Seek the spaces where curiosity still burns, whether in the Institute, a different community, or one you build yourself. Let learning move you again before time, as it always does, moves on.

Mr. Chang is a freshman at Columbia studying political science. He is a staff writer for Sundial.

The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Sundial editorial board as a whole or any other members of the staff.