Summer News Roundup: The Baroness Bows Out

Sundial reacts to President Shafik’s resignation and the legacy of her leadership at Columbia.

The following was published as part of Sundial’s Summer 2024 News Roundup, a collection of humorous takes on the news you missed.

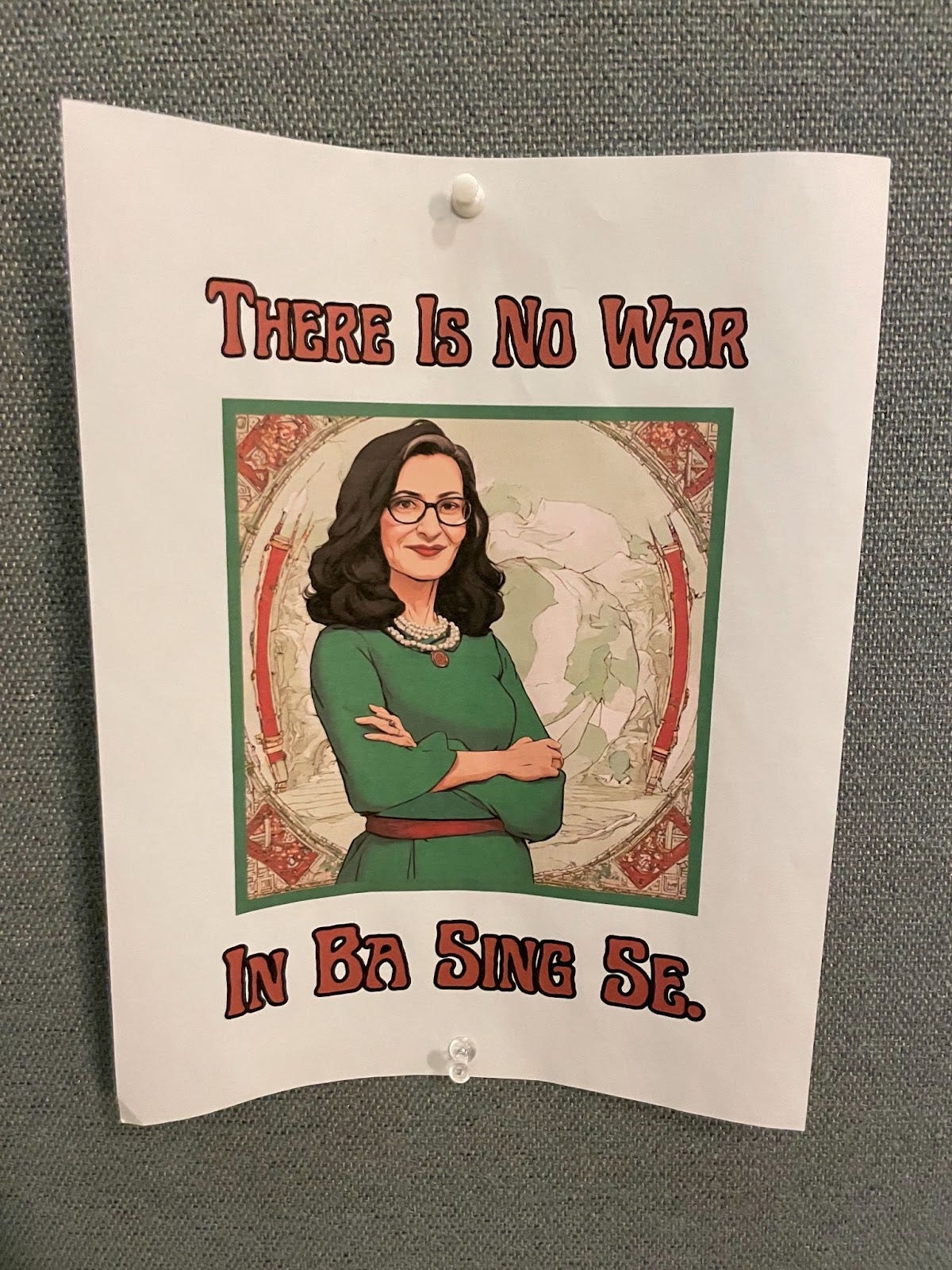

→ There is no war in Ba Sing Se

President Shafik resigns.

In Avatar: The Last Airbender, a city named Ba Sing Se is the epicenter of a brutal war engulfing the otherwise magical world. Yet, within the official city walls all talk of the war is silenced in exchange for bureaucratic pleasantries and a fake feeling of calm, enforced by the administrative overlords and their arbitrary restrictions.

While my editor-in-chief, Jonas, told me that putting this meme here would make me look like a big nerd, spotting it throughout campus back in April put a smile on my face. Like in Ba Sing Se, at Columbia last semester there was very little if any acknowledgement from those in charge that anything was ever that wrong.

But, “Shafik sent in the NYPD, twice,” you say. She sent out near-daily emails, too! Yet, despite her attempts at appearing like she had everything under control, she was always inconsistent in her actions, vastly unclear in her messaging, and never once showed her face until the dust had cleared. In other words, Columbia’s army of administrators, headed by now-former President Minouche Shafik, preferred telling themselves and anyone who would listen that “there is no war at Columbia,” rather than confronting the situation head-on.

Shafik’s emails, which often felt distant and disconnected, would always include platitudes like:

“At this moment, we must rededicate ourselves to our fundamental mission of learning, teaching, and research. Throughout our history, this is how we have made a lasting impact on the world,” she wrote in an April 26 email.

It was a far cry from what was happening on the ground. The evening of April 16 was the last night with a semblance of normalcy—there had been an epic lawn party, complete with a DJ and seniors dancing in their graduation gowns (which, of course, was promptly shut down). Within hours, the first encampment was erected; a day later, the first NYPD arrests occurred, and by that evening a second encampment on the West Lawn was burning brighter than the first, with essential shipments (cigarettes) arriving regularly.

That month, students woke up each morning to the sounds of news helicopters and often had a harder time finding an open entrance to campus than they did getting into a local dive bar without a fake ID. The situation dragged on and on and on, and we as a community were left without any guidance. Perhaps an email would announce that we wouldn’t have in-person class the next day, or that campus would be closed even to most students, or that we should pack up our things and go home. But all of these announcements came without any forewarning, often appearing in students’ inboxes late at night (hello, 2:15 AM email from Shafik!).

On April 18, Shafik said the first NYPD raid was necessary “out of an abundance of concern for the safety of Columbia’s campus.” Eight days later on April 26, she sent another message saying that “bring[ing] back the NYPD at this time would be counterproductive,” before calling the NYPD yet again on April 30, claiming once more that “my first responsibility is safety.” Although Columbia’s encampment was a nationwide first, the administration didn’t take the lead on establishing consistent principles for addressing safety concerns and utilizing law enforcement.

Shafik was, similarly, either noncommunicative or inconsistent regarding dialogue with the protest organizers. On April 22, she said she planned on “continuing discussions with the student protestors.” Her office regularly said the talks yielded “progress” over the next few days, but suddenly we were told on April 29 that the administration was not able to come to an agreement with the protestors and that they would be pursuing “alternative internal options.” During the course of the negotiations, never once were we told what the administration’s non-starters or other conditions were.

Even when Shafik provided simple acknowledgements of how divided campus was, it was always devoid of any appreciation for how serious the situation was.

“It is going to take time to heal, but I know we can do that together. I hope that we can use the weeks ahead to restore calm, allow students to complete their academic work, and honor their achievements at Commencement,” Shafik wrote in a May 1 email, hours after the second NYPD raid. Her office canceled said Commencement’s main ceremony only five days after making this statement.

On May 3, Shafik released her first speech since the start of the encampments in a recorded video. All she had to say after sending home the entire school was “we have a lot of work to do” in about ten different ways. After waiting for weeks for a strong statement from a leader, the propriety was simply unbearable—students were understandably upset that she had posted a dispassionate video (on Vimeo of all places!) of her essentially smiling in a garden as if nothing had happened.

Even more, the absence of a strong leader throughout the episode opened the door for other “outside agitators,” such as House Speaker Mike Johnson, to use the situation to their advantage. On April 24, Johnson, on the steps of Shafik’s own office, called for her resignation “if she cannot immediately bring order” and then invoked the possibility of bringing the National Guard to campus. (Managing Editor Henry Oltman had similar sentiments on Johnson’s press conference in our April-May issue.)

A Cardboard Calm

After last semester’s climactic finish, Columbia plunged into a summer of nothingness. Shafik sent one message on July 8 regarding the text message scandal between four Columbia deans, and on July 24, Shafik shared some steps that the University would be taking to “sustain the educational and research mission of this university while reestablishing our sense of community.”

But for the most part, the administration has tried to once more paint a picture of Columbia as a calm and, frankly, boring place where nothing ever happens—especially not protests. The school’s Instagram account made over 90 posts since students left campus in May, featuring sunsets, flowers, and Olympians—attempts at making the student body and the greater public simply forget about the past semester and move on without batting an eye.

Despite their efforts, amongst students there was a palpable silent apprehension. The summer’s mounting anxiety was met with one final surprise announcement: Baroness Shafik had resigned.

Her resignation took the form of one last email, dated August 14:

“This period has taken a considerable toll on my family, as it has for others in our community,” Shafik wrote. “Over the summer, I have been able to reflect and have decided that my moving on at this point would best enable Columbia to traverse the challenges ahead.”

It is hard not to feel at least some pity for Shafik, who started her term without any indication that within several months, war in the Middle East would cause a total implosion at Columbia. But as the leader of a heterogeneous organization, she attempted to do the impossible when she set out to please everyone. When you try to appease every side with official-sounding proclamations and constant capitulation, you lose every supporter you may have once had.

If this episode has taught Columbia’s administration anything, it should be that you cannot fight turmoil with flowery language and vague hopes for conflict resolution. You must be clear with your words and even clearer with your actions.

Put a Southerner (Katrina Armstrong) in the White House (Low Library)

At the time of writing, Columbia students have already begun moving into dorms, and the competing messages for Interim President Katrina Armstrong have already begun.

“This is not going to be a golden ticket to a magically repaired institution,” Eden Yadegar, former president of Columbia Students Supporting Israel, told Sundial. “Under President Shafik’s leadership, or rather the lack thereof, antisemitism, anti-Americanism, and, frankly, anarchy, were allowed to take control of the university.”

Meanwhile, Columbia Students for Justice in Palestine said on X that Shafik “finally got the memo” after months of protest. “Any future president who does not pay heed to the Columbia student body’s overwhelming demand for divestment will end up exactly as President Shafik did,” they added.

The school’s leadership, including the interim president, must be ready to immediately face the university’s crisis head-on, without mincing words and without constant capitulation.

“The University exists because of the love for the institution expressed and the contributions made by countless talented individuals over many decades, particularly our faithful alumni,” Armstrong said in an email shortly after Shafik announced her resignation.

Armstrong’s word salad from her first message to the community as interim president might be a troubling sign of how ingrained officialese is in Columbia’s leadership, but I’m willing to just chalk it up to her being a doctor.

Armstrong may have an ace up her sleeve, though. She is from Alabama and paid for her own tuition as an undergraduate at Yale. She knows what it's like to be in touch with real, down-to-earth people from a variety of backgrounds, and her research heavily reflects that. And, I believe that a heavy dosage of candor and Southern charm might just be what it takes to break this spell of out-of-touch and inconsistent leadership at Columbia.

Mr. Cheramie is a senior studying history and Classics at Columbia College and the managing editor of Sundial.