Shafik and Armstrong’s Emails were Statistically Bad

I conducted readability tests on Katrina Armstrong and Minouche Shafik’s University-wide emails. The results are concerning.

Columbia students may disagree with each other on a lot of subjects, but if there’s one thing that unites us all, it’s our shared hatred of the unreadable emails from former presidents Minouche Shafik and Katrina Armstrong.

Take this paragraph from Armstrong’s March 15 email, entitled “Standing Together for Columbia”:

Our University is defined by the principles of academic freedom, open inquiry, and respect for all. These principles are fundamental to Columbia’s broader mandate of advancing the betterment of our community, our city, our country, and the world. We will defend these principles with courage and determination. It is because of these values that Columbia serves the world so well. From Alexander Hamilton to Dwight D. Eisenhower to the present, we teach, we heal, we innovate, and we create knowledge. To damage Columbia is to weaken American ingenuity and leadership.

This could have been simplified to:

Columbia stands for academic freedom, open inquiry, and respect for all, core values that fuel innovation, leadership, and the public good.

And this passage from Shafik’s January 17, 2024 email, entitled “A New Social Contract: Sharing our Strategic Priorities,” is just as verbose:

In the realm of academic excellence, our objective is ambitious—to elevate all of our schools to be research and educational leaders in their respective fields. We aspire to make major intellectual contributions in areas of paramount importance such as climate, artificial intelligence, and mental health where Columbia has huge comparative strengths. Lifelong learning will be a cornerstone, ensuring that access to a Columbia education is available to people throughout their lives. Global and local engagement will remain at the forefront, forging connections and collaborations that transcend borders and deliver real impact.

With paragraphs this dense, it would be surprising if even 20 percent of the student body made it past the first few lines, let alone read the whole thing. Sundial has already critiqued the administration’s poor communication strategies, and Bwog has analyzed Armstrong’s emails to determine if they are AI-generated. Critical analyses like these are an important check against administrative bureaucracy, but I think we’ve missed an even bigger question: what are those emails even saying?

We know they’re poorly written, but why? Is it the word count or sentence length? Is it the content? I decided to do some research and see if there was a way to quantitatively answer these questions.

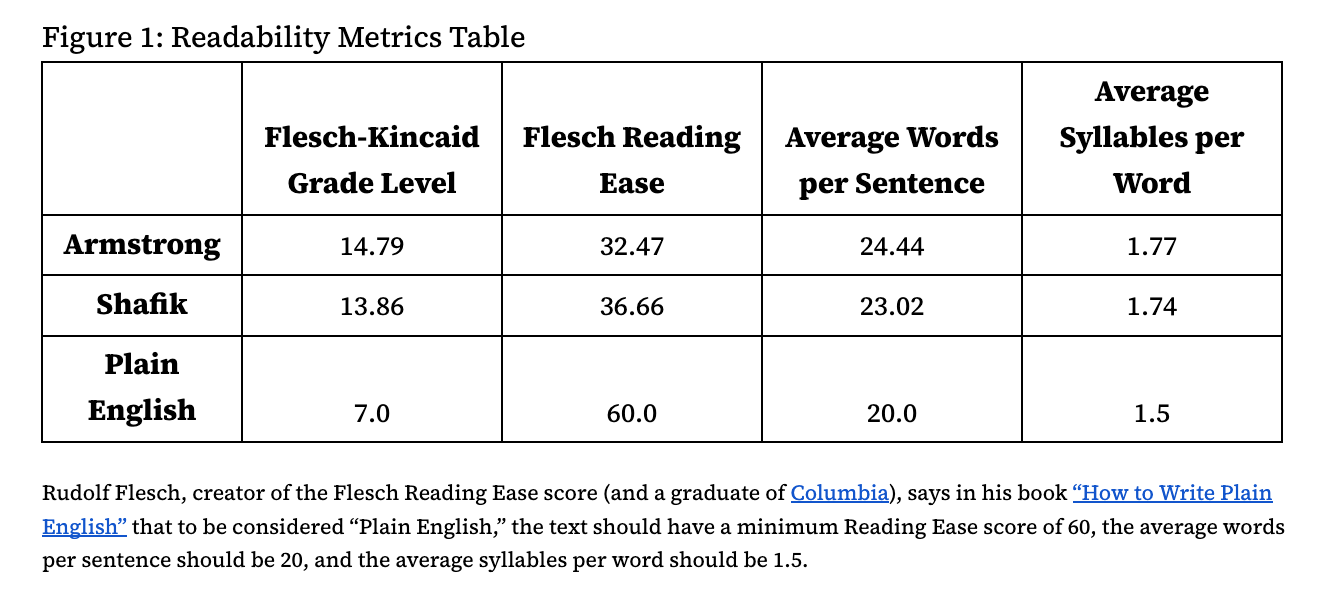

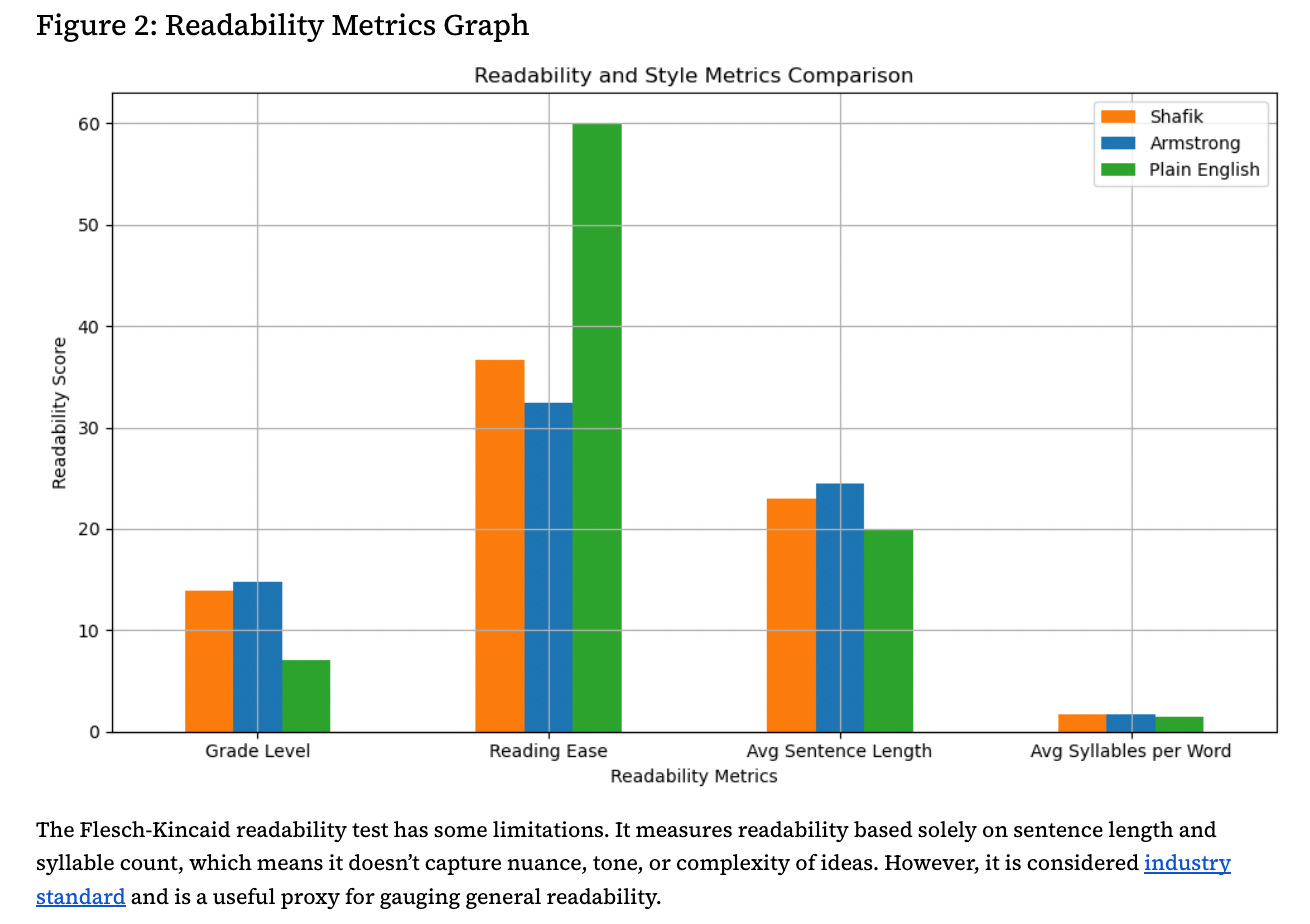

I compiled every protest-related email from Shafik and Armstrong’s presidencies (45 in total) and ran them through two analyses. The first was the Flesch-Kincaid readability test, which measures how difficult a text is to read. It generates two main scores: the Flesch Reading Ease score and the Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level. The Reading Ease score ranges from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating easier readability (e.g., scores above 60 are easily understood by most people, while scores below 30 are considered difficult). The Grade Level score translates this into a U.S. school grade level—for example, a score of 12.0 means the text is expected to be understandable by a 12th grader, 13.0 by a college freshman, and so on. Both scores are calculated using a formula based on the average sentence length and the average number of syllables per word. In short, longer sentences and more complex words mean the text is harder to read.

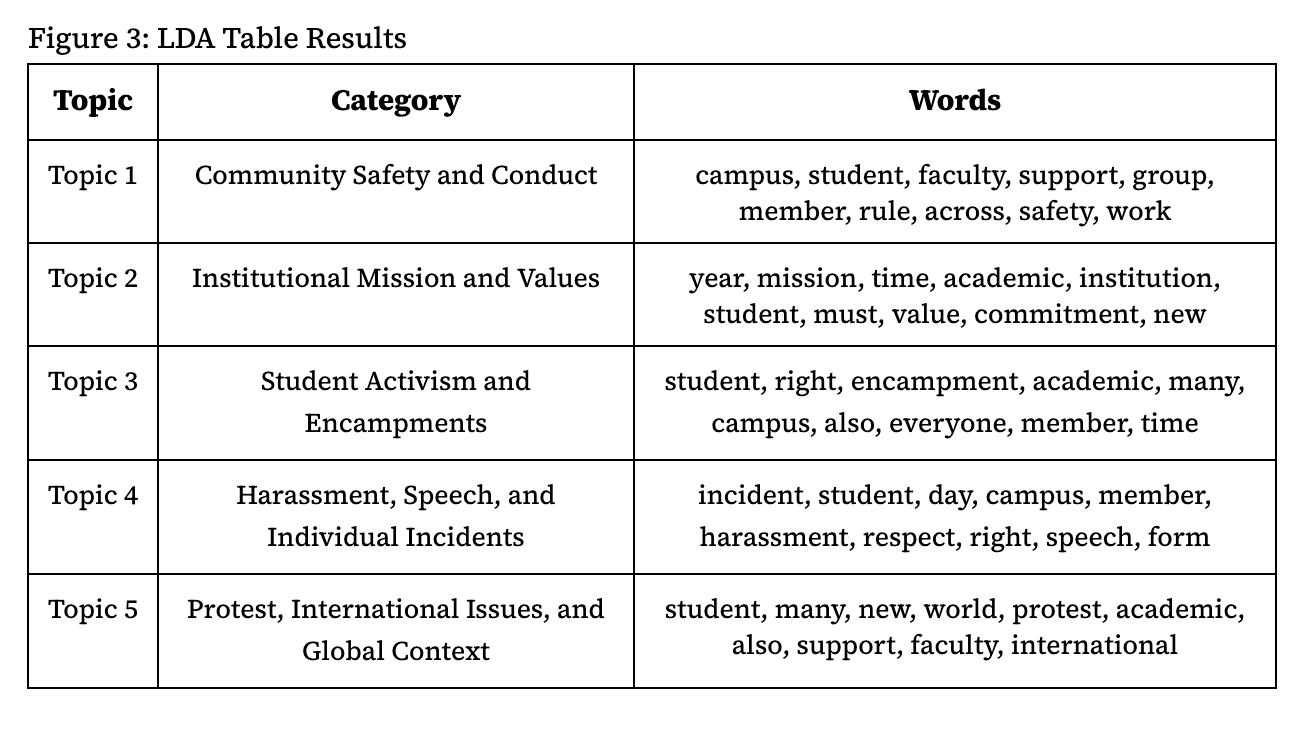

The second method of analysis I implemented was Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA), a machine learning method that identifies themes in a collection of documents. It assumes each document is composed of a mixture of topics and identifies those topics by analyzing patterns in word usage and frequency.

Think of LDA like attending a party where you can’t hear full conversations, only snippets of words. Instead of trying to follow what any one person is saying, you listen for words that tend to show up together: “guitar,” “band,” and “tour” might suggest a conversation about music, while “election,” “policy,” and “voters” point to politics. By grouping these word clusters, LDA uncovers the hidden topics people are discussing, even if no one says the topic explicitly.

Flesch Kincaid Results

While the similarity of Shafik and Armstrong’s email grading may seem suspicious, remember that they are cut from the same cloth: Both have extensive academic backgrounds, so it’s no surprise that their writing styles mirror that of a research paper.

This serves as a reminder, especially for us Ivy Leaguers, that more words do not always make for better writing. With an average Reading Ease score of 34.56/100 and average Grade Level score of 14.33, these emails are rated as “difficult” to read and considered “college” level. Yes, we are college students at a rigorous academic institution, but mass emails addressing urgent campus issues should not be written at the same level as the Harvard Law Review. These emails are read not only by students, but also serve as official communications for the press and the general public.

For context, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) recommends that the readability of public-facing texts “should not exceed 7th to 8th grade (average),” and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Clear Writing Hub website states that “the more words you use, the longer your sentences, the more pages you write, the less likely your reader will understand or stick with you.”

I’m not asking our next president to write at a 7th-grade level. But with sentences averaging over 23 words (the government recommended length is 15-20 words per sentence), these emails read like they were composed by a committee of legal professionals, and then reviewed by a PR team that forgot that Gen Z students—with our 8-second attention spans—are the target audience. It’s not so much communication as it is linguistic liability management.

LDA Topic Results

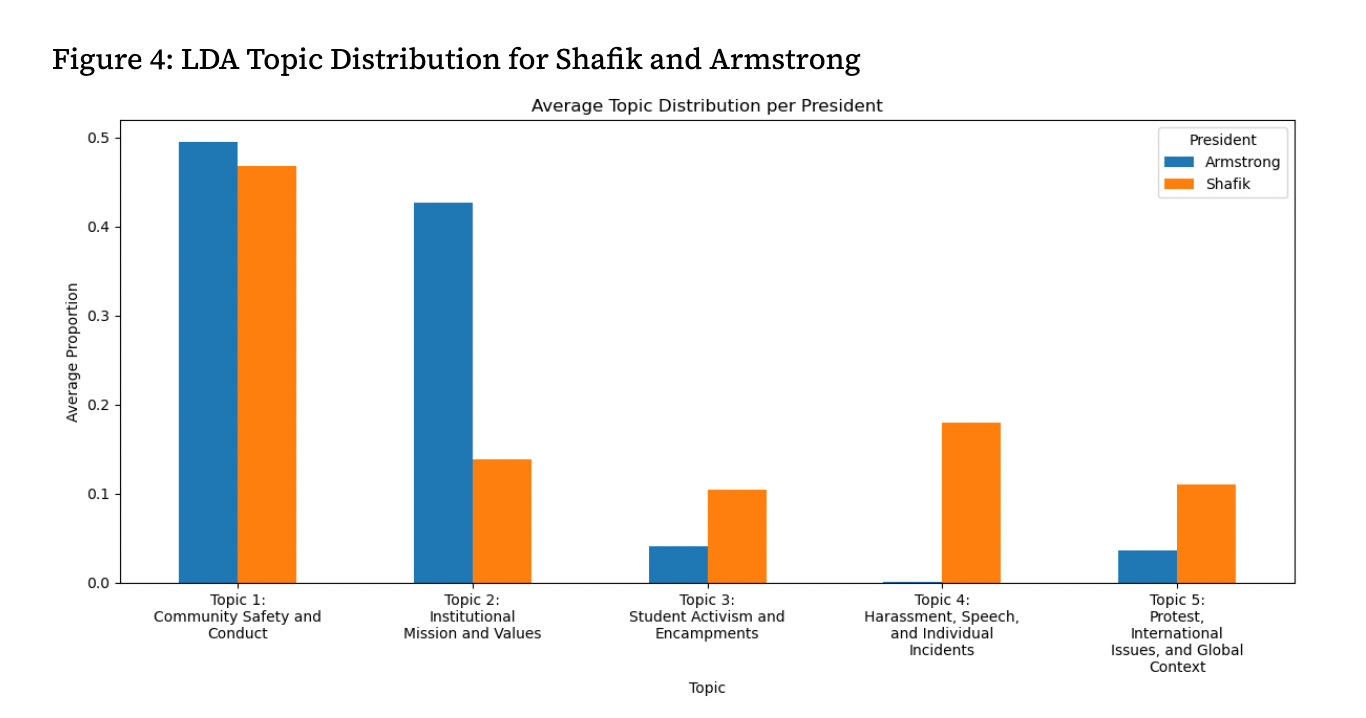

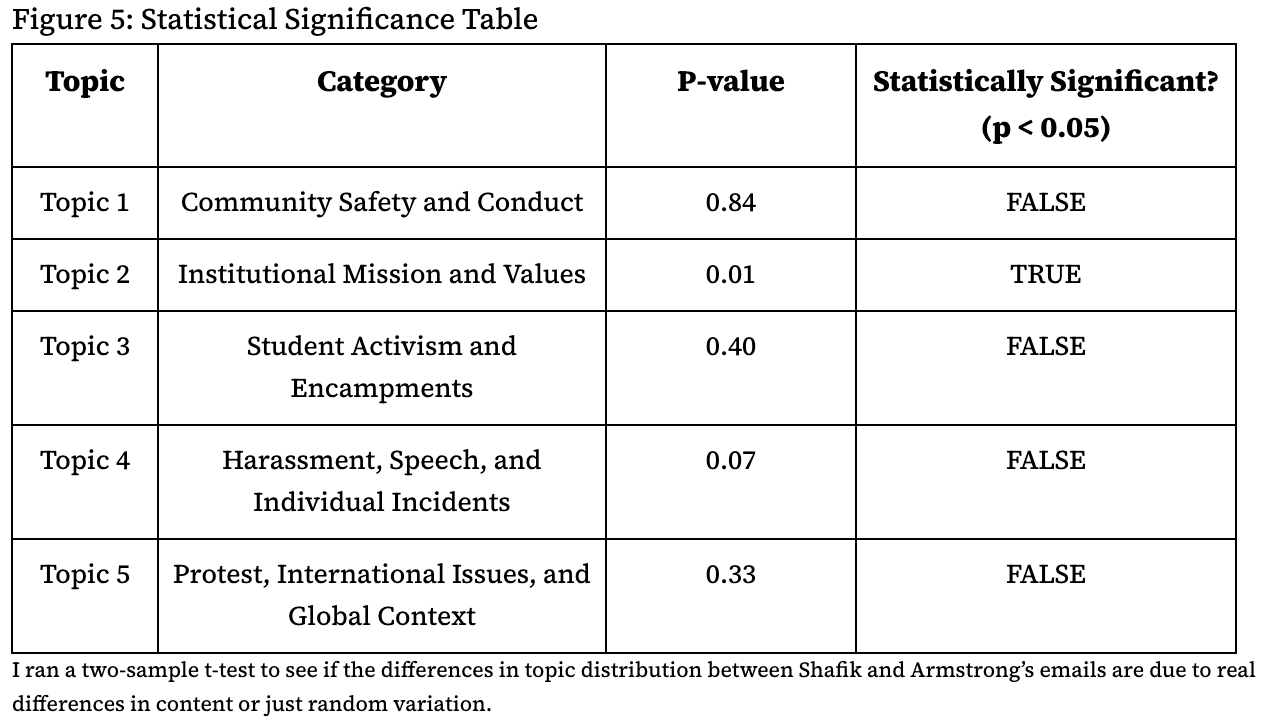

The LDA model reveals a split in administrative focus. Shafik emphasized student activism, harassment, speech, and protest slightly more than Armstrong. This is understandable, given the encampments and spike in antisemitic incidents on campus following the October 7 Hamas attacks. On the other hand, it seems that Armstrong made a concerted effort to prioritize “Columbia’s values,” no doubt in response to the events of the previous year and the Trump administration’s scrutiny of the University. Nearly half of each president’s emails were centered around campus safety, reflecting how heavily the issue shaped their messaging.

The only statistically significant (p < 0.05) difference in emphasis between Armstrong and Shafik appears in Topic 2, indicating that Armstrong more deliberately framed her messaging around “Columbia’s mission” and “core values” than Shafik did.

In context, this divergence makes sense. However, the important question isn’t about what Shafik and Armstrong focused on in their communications. It’s about what they did. Despite their rhetorical differences, both leaders followed the same pattern of saying the right things but causing little change.

This pattern becomes clearer when we examine the initiatives Shafik and Armstrong oversaw. What happened to the Task Force on Antisemitism? Since its inception under Shafik’s administration in November 2023, they have produced two reports, the most recent published on August 30, 2024, and there has been little communication about implementing the task force’s recommendations.

Then there’s the mask mandate. Armstrong publicly committed to enforcing a ban on face coverings at unauthorized protests, while privately assuring faculty she had no intention of doing so. And what about the President’s Advisory Committee on Institutional Voice? Armstrong announced the creation of this committee on September 17, 2024, but waited another five months to tell us that “The Committee anticipates completing its work and providing a report to me by the end of the current academic year.” Imagine creating an entire committee to help you do your job, only to be ousted before it accomplishes anything. Ouch.

All this is to say that these blunders aren’t just political mistakes: They reveal a deeper pattern of performative leadership, where a lack of tangible results routinely undermines stated commitments. This, more than anything else, is the core issue. Despite using the words “principle(s)” and “value(s)” a combined 73 times across 45 emails, Shafik and Armstrong did not act upon the principles and values that guide this institution; they only wrote about them.

Sure, the Listening Tables and Dialogue Across Difference initiatives may have been helpful. But in an institution as bureaucratic and slow-moving as Columbia, these efforts are rendered ineffective if the basics of leadership—clear communication and following through with commitments—aren’t practiced.

I recognize that it is incredibly easy for me to critique Shafik and Armstrong when I have very little idea what they were dealing with behind closed doors. It’s a tough job, and no president will ever succeed in pleasing everyone. But maybe that’s the answer. Columbia needs a president who understands that they will not be able to make everyone happy. It may be prudent for Columbia’s trustees to find a candidate less entrenched in academia, perhaps someone who has experience making high-stakes, tough decisions. Most importantly, though, we need a president who knows how to communicate effectively. If they can’t even exercise that basic skill, there’s no way they’re going to be able to lead Columbia.

Link to Emma’s code: https://github.com/es098712/Columbia-President-Emails

Ms. Shen is a junior at Columbia College studying financial economics and computer science. She is a senior editor for Sundial.

So much good stuff in here 🔥