Orienting Ourselves With "Disorientation"

What the activist pamphlet circulated during the first weeks of school can teach us about the importance of pro-Palestinian thought at Columbia

Stepping onto campus this fall, I saw the many ways in which the administration welcomed new students: barbecues, merchandise giveaways, balloons adorning campus, all of which exist as parts of, or accessories to, Columbia’s annual University-wide orientation programs. Implicit in the program is a sanitized story of Columbia, a narrative that spotlights the Core Curriculum and the allure of New York City. Understandably, from the administration’s point of view, digging into all the recent events—the protests, legal brawls, presidential turnover—would kill the vibe.

But, from a flyer distributed by an undergraduate, I stumbled across another orientation: “Disorientation,” an anti-orientation program that offers a less rose-colored depiction of our University. Unsure as to who put it together, I asked for the contact information of the student who handed me the flyer to inquire further about this new initiative. I will refer to him as Gabriel for anonymity purposes.

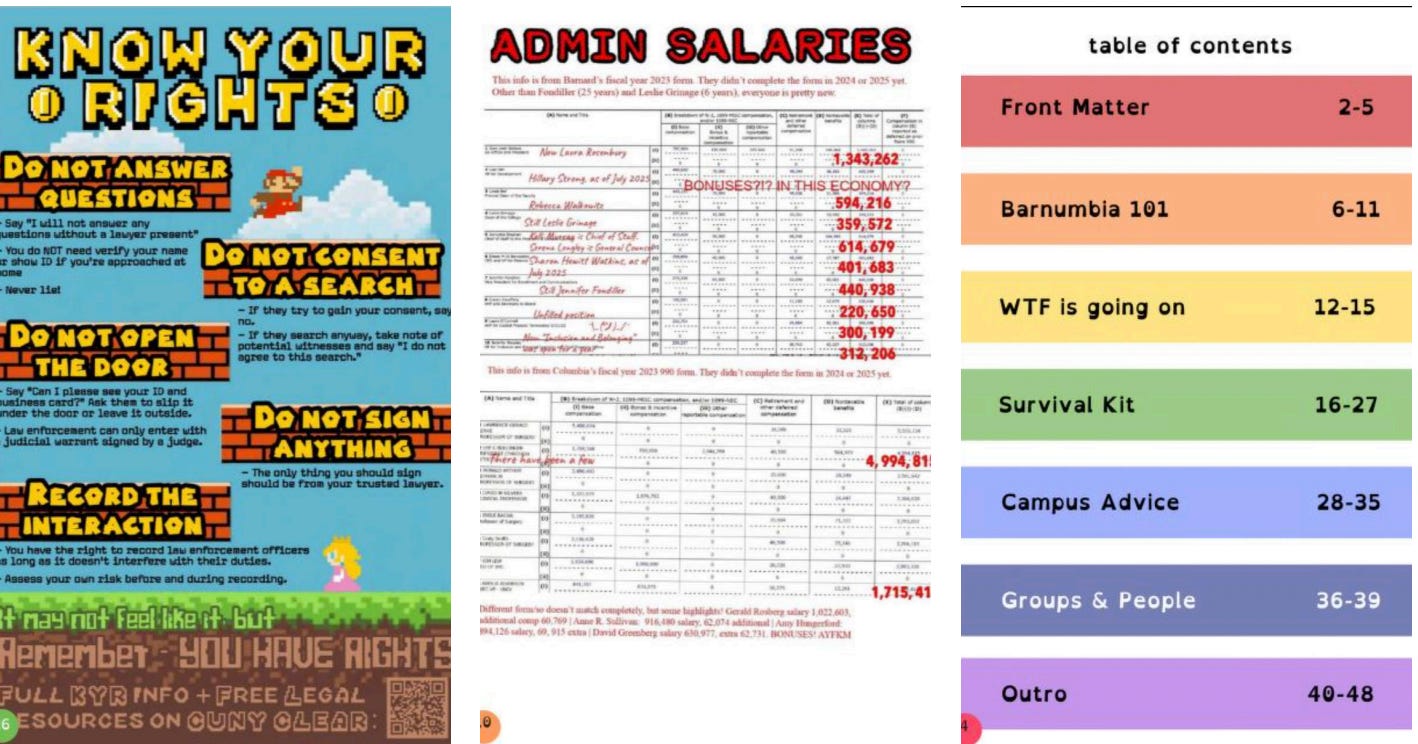

According to Gabriel, the program has two prongs: a paper guide and a series of teach-ins. The student sensed that the guide was put together by former students from Palestinian-sympathizing groups such as Columbia University Apartheid Divest (CUAD), though the actual authors have remained anonymous. The teach-ins, on the other hand, involve a wider coalition of activist-minded groups, including Students for Justice in Palestine (SJP), Columbia-Barnard Young Democratic Socialists (YDS), and the Student Workers of Columbia (SWC).

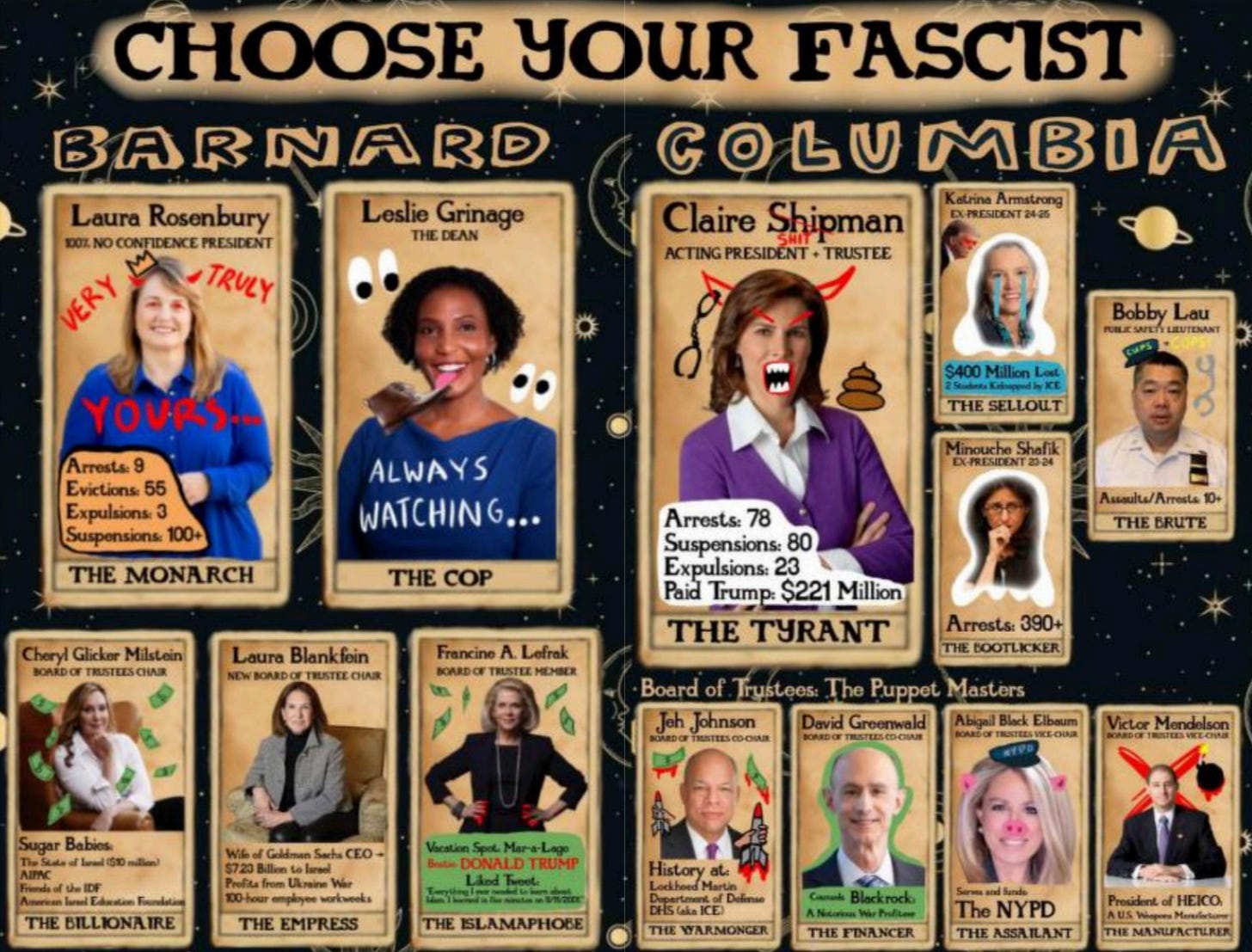

Flipping through the pages of the guide, it initially appeared to be performatively progressive, an amalgamation of what a conservative might laugh off as “woke garbage.” It opens with a Native American land acknowledgement, the seventh page features President Shipman with horns, and the middle of the booklet categorizes police officers into different types of pigs.

For much of my time at Columbia, these types of messages felt hackneyed and inescapable—no more than expressions of an intolerant and reductive left. However, I have come to appreciate the current necessity of the guide.

Before, these activist messages felt inescapable. Yet now, in the face of a shifting campus climate, they feel more hidden and less ubiquitous. Broad swathes of Columbia’s pro-Palestinian coalition have been sanctioned. Personally, the only protest I’ve seen took place on October 7. For these reasons, Columbians who would otherwise advocate for Palestine have dimmed their activism from fear of suspensions, losing visas, and, for international students, detainment.

But in the midst of this unprecedented new era at Columbia is the “Disorientation” guide: an attempt to reincarnate, at least in part, the now-neutered Palestinian movement on campus. It captures the tenor of the activism we saw last year, providing death counts from Gaza, and highlighting polling numbers showing a majority of students in favor of divestment.

This is why the guide is so vital in this moment: It exists as the most robust embodiment of the Palestinian cause right now at Columbia. Of course, members of our community still write opinion pieces and engage in political discussion. However, an anxiety underpins the movement, stifling the shrill confidence that once defined it.

Many would view this pamphlet, as well as the protests themselves, as existing outside the sphere of discourse, and thus, not something we should engage with. But that logic follows a reductive definition of discourse. All of these modes of expression—the table conversations, the brazen activism, the disembodied pamphlet—constitute discourse, though, admittedly, not in identical ways. Because of this, we should read it.

Naturally, the pamphlet is less than ideal. If one of its pages sets us off, we wouldn’t even know who to argue with. Nevertheless, it captures the ideology of a large coalition of students on this campus. It encapsulates how they feel and how they’ve reflected on recent events. Do these types of insights not overlap with some of those we gain from, say, a table conversation, at least in part?

Moreover, invoking some of the traditional arguments in favor of unconstrained speech, we are still improved by a confrontation with ideological opponents insofar as it helps us refine our own convictions or gives us a chance to inch closer to the truth. In this regard, the pamphlet is a part of our discourse, and we should attend to it. Additionally, we should keep in mind what happens when a coalition is fully forced underground. When actively silenced, ideas grow more ferocious, myopic, and radical. This is not what we want.

Even beyond Palestine, however, something has shifted on campus, and speaking with Gabriel confirmed this instinct. From his vantage point, the dismemberment of the Palestinian coalition wasn’t completely surprising, especially given some of its members’ extremism. What is surprising, though, is the dissolution of the broader activist ethos on campus. In his view, groups that see themselves as wholly distinct from the Palestinian cause are feeling constrained in their capacity to protest as well.

On the phone, we talked about a “Disorientation” gathering that was planned for Sept. 3 in Riverside Park. Gabriel later informed me that it was cancelled for reasons that aren’t entirely clear, and that even non-Palestinian student activist groups feared that they could be sanctioned by the University for participating in the gathering. From Gabriel’s perspective, this moment captured the new posture from the administration, a stamping out of all types of protest.

In part, this response from the administration makes sense. However, returning to the idea of safeguarding all manifestations of discourse, this shift feels disconcerting. A protest-obsessed campus culture, naturally, can result in the inability to process nuance. Yet we also lose something critical without student activism. Students can find community in protest, become invested in political issues that they wouldn’t otherwise consider, and use political mobilization as a form of catharsis and as a space to effectively express grievances to the administration or even the president of this country.

With this activist culture, many feel frustrated. But without it, we will not turn out better. Protest is integral to dialogue—it provides a space for students to coalesce around ideas, to develop a greater engagement with those ideas. It’s not perfect, but activism enriches the conversations we have on campus. It doesn’t diminish them.

Mr. Gill is a second-year at Columbia Law School and a 2022 graduate of Columbia College. He is a staff writer for Sundial.

The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Sundial editorial board as a whole or any other members of the staff.

For those interested in submitting a response to this article, please contact us at columbia.sundial@gmail.com.