No, Columbia Is Not a Democracy

The Student Affairs Committee misrepresented the Statute amendments. It’s time to set the record straight.

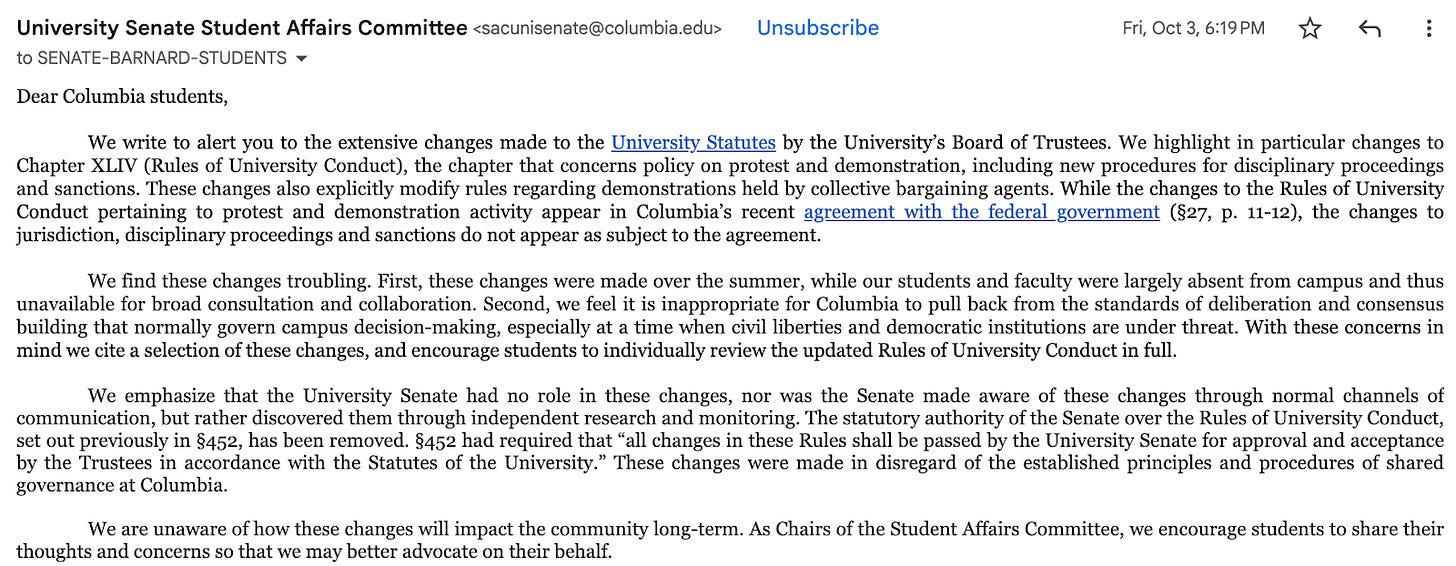

On October 3, Columbia’s Student Affairs Committee (SAC) notified students of revisions made to the University Statutes. The updated policies were introduced pursuant to Columbia’s settlement agreement with the Trump administration, which consolidated disciplinary authority under the Provost’s office and stripped the University Senate of its jurisdiction over the Rules of University Conduct.

The SAC opposed the amendments, arguing that they were adopted without broad consultation, circumvented the Senate’s traditional advisory role, and included provisions that disregard “the [University’s] established principles and procedures of shared governance.”

The Committee succeeded only in sowing paranoia among students, casting routine policy reforms as harbingers of Columbia’s inexorable descent into fascism. A cursory examination of the Statutes reveals their claims as entirely contrived.

Take their primary grievance: “We emphasize that the University Senate had no role in these changes, nor was the Senate made aware of these changes through normal channels of communication.”

This is technically true yet substantively meaningless. The SAC cites Section §452 of the Statutes, which previously required “all changes in these Rules” to pass before “the University Senate for approval and acceptance by the Trustees.” This provision was eliminated before Columbia abolished the Senate’s purview over the Rules of University Conduct.

In other words, by the time the Board of Trustees modified the Statutes, the Senate’s authority was already null. The SAC’s framing neglects the revocation of said “principles” months prior.

Critics might reasonably ask why Trustees nixed consultative conventions, if not as an opportunistic maneuver.

One need only examine the Senate’s track record. In March 2025, it published the anonymously-authored Sundial Report (unrelated to this publication), bypassing dissenting senators. According to the University website, the report “provides a day-by-day timeline” of campus protests from October 2023 through December 2024.

The Senate’s timeline is neither complete nor accurate.

On April 30, The Stand Columbia Society released the Sunlight Report, a revised edition enumerating 470 errors in the original 1,273 claims. As Noam Woldenberg and I reported in May for Sundial, Senate Executive Committee Chair Jeanine D’Armiento publicly conceded that “the report was published online and circulated to the press without notifying many of the Senate members who ostensibly authorized it.”

Such contempt for protocol appears habitual. Subpoenaed records obtained by the House Education and Workforce Committee revealed that the University Senate’s Rules Committee “reviewed” a disciplinary case and “found no violations of applicable policies.” Yet University Statute §444(b) stipulates that “only the University Judicial Board” is “empowered to determine whether the actions of the accused were in violation” of the Rules.”

The Rules Committee has no power to adjudicate cases or issue findings. It did both anyway.

Meanwhile, when the administration acts within its jurisdiction, the Senate cries foul. In May, D’Armiento told the New York Times, “The Senate has spent a lot of time asking that the rules be followed. And we do see ourselves as not taking, actually, a side. Maybe people don’t believe us, but it’s all about the statutes for us.” Rich coming from a woman who ran for a fourth term in contravention of the Senate’s own bylaws.

Rhetoric versus Reality

Procedural objections aside, the SAC maintains that the revised statutes lack “specifics about permissible time, place and manner of protests.”

Consider what the new Rules actually prohibit:

1) Demonstrations “inside academic buildings and places where academic activities take place” (§442)

2) Masking “for the purpose of concealing one’s identity while violating a University policy or rule or state, municipal, or local law” and “anyone, masked or unmasked” refusing to “present a valid ID when asked by a University Delegate or a Public Safety Officer” (§444)

3) Protest activity in violation of “the University’s anti-discrimination and anti-harassment policies”(§440)

These are textbook time, place, and manner restrictions. The SAC is either unabashedly dishonest or functionally illiterate. Neither possibility bodes well.

The SAC’s email characterizes procedural changes as an “inappropriate” retreat “from the standards of deliberation and consensus building that normally govern campus decision-making, especially at a time when civil liberties and democratic institutions are under threat.”

What were these “inappropriate” amendments?

1) “Disciplinary proceedings may now be recorded on a respondent’s permanent record even if the respondent has been found not responsible for a Rules violation.” The absence of a prohibition is not evidence of a rule. Far from punitive, discretionary recordkeeping establishes behavioral patterns and preserves exculpatory evidence should false allegations recur.

2) The two-month resolution timeframe is now “indefinite,” qualified with the assurance that the University will seek to resolve every report of misconduct as promptly as possible. Proceedings seldom meet two-month deadlines; this modification simply codified an operational reality while ensuring due process.

3) “Respondents no longer have the right to request that a hearing be open to the public.” Public hearings are a crude accountability mechanism. More robust alternatives exist; formal appeals and aggregated data can reveal systemic disparities without compromising students’ privacy. Columbia could and should commit to publishing anonymized disciplinary metrics and mandating periodic independent procedural audits. In any event, confidentiality insulates both parties from public scrutiny.

Apparently, Columbia’s worst offense was relinquishing the Senate’s disciplinary power. To understand why the SAC’s invocation of “shared governance” rings hollow, look no further than the Senate’s original mandate—and how far it has strayed.

The University Senate: A Primer

Established in 1969, the University Senate was intended less as a democratic forum than as an instrument of cohesion. Senate members were expected to represent their constituencies while acting in the fiduciary and institutional interests of the University. With the University President serving as presiding officer, the Senate was conceived not as a foil of administrative power, but as its supervisory apparatus.

Its design was elegant. Alas, the same cannot be said for its execution.

Absenteeism proved corrosive. As the Stand Columbia Society observed, “recent Presidents have largely disengaged from the University Senate’s activities.” President Shafik “attended only three of the twelve sessions during the 2023-2024 academic year.” In lieu of presidential engagement, “the Senate has shifted from being a part of University leadership to something more akin to a ‘counterweight’, or even ‘opposition’, to that leadership.”

The Senate’s devotees argue that this renders it a more effective safeguard on executive power. But this notion presupposes that self-governance is the University’s raison d’être. Columbia is not a commune in which homework is abolished, curricula reshaped, or resources redirected per majority rule. Quasi-democratic bodies like the Senate may exist as consultative forums, but they are ultimately subordinate to the Trustees. Their fiduciary duty does, at times, encompass consideration of the public interest, but that cannot supersede institutional priorities. Ultimately, the Senate’s adversarial posture corrodes the cooperative ethos of higher education.

The result? A body that has devolved into what University Senate manager Tom Mathewson once called “a cargo cult, with an array of powerful but underused legislative customs and procedures.”

Trustees and administrators “blamed” senators for “delaying and obstructing discipline of pro-Palestinian demonstrators who broke university rules”. In February 2024, emeritus board chair Jonathan Lavine told co-chairman David Greenwald that if the Trustees imposed time, place, and manner restrictions “and then have the antisemites on the Senate in charge of discipline and enforcing it, it will also fail.”

In a separate exchange, Columbia College Dean Josef Sorett texted Journalism School Dean Jelani Cobb: “Senate sounds like CUAD” (Columbia University Apartheid Divest). “It’s a spinoff,” Cobb replied.

The Senate’s erraticism validated administrators’ concerns. The New York Times reported that Senate Chair D’Armiento “led a team of faculty negotiators during the encampments and destructive occupation of Hamilton Hall, hoping to forge a compromise with the students,” and that:

The senate did not support police intervention to end the pro-Palestinian encampment last year. It pushed to handle protester discipline [through] a senate-run judicial board, which gives students the right to lawyers, rather than ceding discipline to administrators. The protesters who took over Hamilton Hall were not expelled until 11 months later, a delay that put Columbia in the cross-hairs of Congress and the Trump administration.

The 11-month delay was an inevitable consequence of subjecting imminent institutional needs to deliberative processes. Democratic bodies require consensus, viewpoint diversity, and protracted debate. These are virtues in a legislature. They are liabilities for a University in crisis.

What The Spectator Didn’t Tell You

Nearly three weeks after the SAC’s email, on October 22, The Columbia Daily Spectator published an article titled “Columbia quietly changes rules governing protests and discipline for first time in 10 years.”

Among the senators featured was Professor Joseph Slaughter, who at the Senate’s October 3 Plenary “expressed his concern that the presentation had to come from the Student Affairs Committee as opposed to the Provost’s office,” denouncing it as a “real dereliction of duty on the part of the administration.”

Spectator’s coverage failed to acknowledge Slaughter’s complicity in the very protests that gave rise to the Statute amendments. Though he denies involvement, photos and metadata reviewed by The Washington Free Beacon on April 29, 2024, captured Slaughter conversing “with protesters outside Butler Library, the site of the encampment, while holding one of the neon vests worn by protest marshals.”

On October 9, 2024, Slaughter delivered a lecture lauding the 1970 Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) hijackings—during which terrorists seized five commercial planes and held 310 passengers hostage—as “spectacular” and “remarkable.” Weeks before, at a Senate plenary, he “raised concerns about the [Antisemitism Task Force’s] focus being solely on the experiences of Jewish students facing antisemitism.” Ah, yes, because non-Jews famously experience antisemitism.

Slaughter helped draft the August 2024 Guidelines to the Rules of University Conduct, which the SAC sought to enshrine in the statutes. He voted to expedite protest organization, authorize masking, and shield interim-suspended students’ access to housing and dining. The same professor who emboldened violent agitators, extolled terrorists, and objected to the Antisemitism Task Force’s centering of Jewish students’ experiences audaciously berated the Trustees’ “dereliction of duty.” Go figure.

Spectator also quoted University Senator Michael Thaddeus, Professor of Mathematics and Acting President of Columbia’s chapter of the American Association of University Professors (AAUP): “When they [the statutes] are modified, there should be a consultative process, there should be some explanation about why they’re being modified, and it should be done in a transparent way, where you can see all of the different versions.”

He continued: “For decades, demonstrations have been allowed indoors, and demonstrations have taken place indoors, and there are times when it’s totally appropriate to have demonstrations indoors. That can be the only way to accomplish the intended purpose of the demonstration in some situations.”

Thaddeus’s credibility is undermined by his own misconduct—conspicuously absent from the Sundial Report. Nowhere does it mention him commandeering a faculty-wide mailing list to levy ad hominem smears against Columbia College senior Elisha Baker, whom he branded a “right-wing provocateur.”

Amy Hungerford, Executive Vice President and Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, subsequently condemned Thaddeus’s mudslinging.

On November 2, Columbia College students and University senators Liane Bdair and Elizabeth Adeoye published an op-ed in Spectator, recycling the SAC’s talking points with remarkable fidelity.

The senators lament restrictions on “any form of indoor protest,” claiming they “place an undue burden on the students who aim to enact their right to freedom of speech.”

As a private university, Columbia is not directly bound by the Constitution. At any rate, the First Amendment does not guarantee protesters’ freedom of venue. Universities need not sacrifice functionality to accommodate preferred protest tactics.

The senators’ objection to masking provisions is similarly misguided. They insist that the new rule is “overly vague and nearly impossible to enforce fairly” and “there is no clear way to determine intent, whether a student is masking for health, religious, or personal reasons, leaving wide discretion for arbitrary enforcement.”

That is absurd. Intent, here, is assessed as it is in virtually every legal and disciplinary context: through evidence, circumstance, and behavior. If you wear a KN95 while peacefully attending class during flu season, you’re protected. If you don a balaclava while vandalizing Butler Library, you’re not.

Their argument collapses under the weight of its own hyperbole. Bdair and Adeoye allege that said restrictions “reinforce an invasive culture of surveillance under the guise of safety and put all students at risk, whether engaged in activism or not.” “Surveillance” implies preemptive monitoring, not the foreseeable consequence of flouting University Rules in plain view. By their deliriously expansive logic, quiet hours, fire codes, and guest registration policies all constitute “surveillance.”

Apparently, we’ve stumbled into an Orwellian hellscape where rule-abiding students are bootlickers, and the jackboots are none other than President Shipman’s sensible pumps. The senators are playing a rhetorical shell game, and not a particularly sophisticated one.

Case in point, their conclusion: “these guidelines create a hostile disciplinary climate that corrodes the right to protest and instills fear among students and faculty.”

If memory serves, protests tend to be far more “hostile” and fear-inducing than any administrative memo. The amendments they decry merely reassert basic expectations of decorum. If these standards “instill fear,” the problem isn’t the rules; it’s the protesters’ intended conduct.

The senators affirm that “no matter where one stands on any issue, we all have a stake in preserving the principles of openness and shared voice that define Columbia’s history and identity.” They’re correct, which makes their systematic distortion of reality all the more troubling.

The Case for Proportional Governance

Columbia is governed by the Charter of 1810, which grants the Board of Trustees absolute fiduciary power. In May 2024, the Senate passed a resolution declaring that the University Statutes are Columbia’s “constitution,” language it repeated as recently as March 2025. Functionally, however, the charter is analogous to “Columbia’s articles of incorporation,” while “the University Statutes serve as its by-laws.”

The Senate’s rhetorical sleight-of-hand attempts to transmute Columbia from a corporate enterprise into an egalitarian polity.

There is, of course, a practical check on trustee authority. As Professor Isidore Rabi reminded University President Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1950: “We are the university.” If professors feel disrespected, they’ll leave.

Notice who merits standing in this dynamic: faculty. Not student activists. Not even the Student Affairs Committee.

In a May 2024 Balkinization post, Columbia Law Professor David Pozen decried the “presidentialization” of the University (i.e., Shafik’s unilateralism) and advocated for a more “democratic model of internal governance.” Pozen’s colleague, and newly appointed Special Advisor to the President, Professor Joshua Mitts, quickly penned a response, titled “Faculty Governance Requires Faculty Accountability.”

Mitts contends that organizations function best when stakeholders’ incentives align with institutional goals. University operations transcend teaching and research: Administrators must secure endowment returns to maintain facilities and underwrite everything from financial aid to capital projects. Tenured faculty operate under a different set of incentives. Professors’ salaries do not increase when University finances are well-managed. By contrast, administrators are hired, fired, and compensated relative to their performance.

The occupation of Hamilton Hall crystallized this misalignment of incentives. Mitts recounts the story of Mario Torres, a custodian who was held against his will by protestors who called him a “Jew lover” who they vowed to “f*** up.” Torres described being “swarmed by an angry mob with rope and duct tape and masks and gloves.” Few understand the repercussions of shared governance more acutely.

While faculty and student senators deliberated over procedural niceties, Columbia’s maintenance crew bore the brunt of institutional inertia.

When the Senate prioritized consensus-building with protesters over University employees’ safety, it laid bare the moral vacuity inherent in treating all stakeholders’ interests as equally legitimate.

Mitts isn’t making a case against student input or faculty involvement; if anything, he offers a defense of proportionality. Advisory committees are vital, but conferring statutory authority to biased arbiters is untenable.

Columbia is not a democracy. Nor is it a constitutional republic operating under a separation of powers. It is both a corporation with a clearly demarcated chain of command and an internationally acclaimed academic institution with a mission that transcends the whims of students and faculty.

The SAC pretending otherwise doesn’t make it so.

Should Columbia Be More Democratic?

That’s the $221 million question. My peers’ responses ranged from utter apathy to passionate engagement, with most landing somewhere around “Wait, we have a Senate?”

But not everyone was checked out. GS/JTS first-year Sam Almo-Milkin offered a refreshingly earnest perspective: “I have spent my entire educational life at progressively-minded institutions where students, faculty, parents, and administrators collaborated closely with the head of school and board of Trustees on matters of budget, hiring, and curriculum development. In my experience, models of shared governance have led to stronger community cohesion and better long-term financial success.”

Almo-Milkin may be right. Perhaps I’m too cynical. Either way, this much is clear: Debate is futile when one side traffics in lies and omission.

Columbia is at a crossroads. Will it be guided by its stated values or held hostage by a Senate that has abandoned its mandate? Will students recognize the Trustees’ authority or continue to scream “f**k fascism” into the ether?

One path promises a return to an academic community where ideas are contested earnestly; the other perpetuates disruption indefinitely.

Next fall, a new crop of bright-eyed overachievers will arrive believing Columbia’s prestige is osmotic. Four years later, they’ll graduate, joining the ranks of America’s vaunted elite. Whether they leave as educated adults—able to parse a statute, evaluate an argument, or read past a headline—depends entirely on us.

With great power comes great responsibility. Proponents of shared governance must demand more from their representatives, read the statute amendments, and ask the SAC why they overlooked the context that undercut its narrative. Make no mistake: the Senate is betting on our ignorance.

It’s time we call their bluff.

A correction was made on December 10, 2025: The original published version of this article stated that the University Senate “published the anonymously-authored Sundial Report (unrelated to this publication), bypassing dissenting senators in breach of statutory procedure.” The Senate breached statutory procedure in publishing the Sundial Report, though not for bypassing dissenting senators. That’s technically permitted. What they cannot do is bypass the President or Board of Trustees per Section §22(c) of the Statutes: https://t.co/fZ5qNXxbby. The Sundial Report never touched the President’s desk. The Chair admitted publicly that the President hadn’t seen it before its release. This procedural failure alone constitutes a statutory violation: https://t.co/UOTILxMWUC. The article has been edited to reflect this correction.

Shoshana Aufzien is a sophomore at Barnard College and the Jewish Theological Seminary. She is the Public Affairs Co-Chair of Columbia Aryeh and a 2025-26 Campus Transparency Fellow for The Fund for American Studies (TFAS). She is a staff writer for Sundial.

The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Sundial editorial board as a whole or any other members of the staff.

No, it’s totalitarian.

Are there any Goyim for Israel here?