From Morris Hillquit to Zohran Mamdani

What we can learn from the socialist mayoral candidate who ran 100 years ago about the power of slogans, nuance, and free speech.

A controversial four-way mayoral election, a popular socialist candidate, and Columbia University in the news—obviously, I am talking about the New York City mayoral election of 1917.

In what was then declared “the city’s most complex election” and considered the “most extraordinary [political battle]” in recent memory, New York found itself apoplectic about the socialist candidate, Morris Hillquit, the Russian-born Jewish founder and leader of the Socialist Party of America.

Indeed, Democratic socialist candidate Zohran Mamdani often compares himself to “socialist mayor of New York City, Fiorello La Guardia” even though La Guardia ran as a Republican. It is important to turn our attention to New York City’s first actual socialist candidate, Hillquit, and ponder, what can his stance towards free speech, violent rhetoric and electoral politics teach us in the present political moment?

Hillquit, originally a lawyer, devoted his life not only to furthering socialism, but also to defending free speech. He unequivocally opposed violence in both rhetoric and practice to achieve his political agenda. He even amended the Socialist Party’s constitution in 1912 to enable the expulsion of any member who advocated for the use of violence to spread socialism in the United States.

Hillquit ran for mayor following the United States’ declaration that it would enter World War I. A mandatory draft was announced. Pacifism was on the rise throughout New York City, especially on Columbia University’s campus. Anti-conscription student activism faced immediate widespread backlash from the government. On June 1, 1917, federal agents arrested two Columbia students, Charles Francis Phillips and Owen Cattell, and a Barnard student, Eleanor Parker, for distributing anti-conscription leaflets. Hillquit rushed to defend them, arguing that the defendants were neither unpatriotic nor un-American, but rather enthusiastic young idealists who were “preaching the gospel of peace.”

Two weeks later, Leon Samson, another Columbia student, delivered an address at a rally in which he urged all young men “to refuse to stand up and shoot down our brothers.” He advocated for a violent revolt like the 1863 Draft Riot, during which New York faced five days of violence, destruction, and looting. The Trustees of Columbia expelled him several days later. Samson sued them, arguing that he shared his views on his own time, off campus (it was summer break). Yet this time, Hillquit did not rush to defend him or put forward a free speech defense as he had for the anti-draft, non-violent rhetoric of Phillips, Cattell, and Parker. Samson ultimately lost his lawsuit against Columbia.

Then, Hillquit threw his hat into a mayoral race. Similar to our own election, several candidates were plagued by allegations of corruption. New York City was mired in uncertainty with many living in poverty. Hillquit ran on a platform of leading New York in opposition to the war. This was immediately noticed not only by politicians throughout the United States but in Europe as well. The incumbent mayor, John P. Mitchel, cast Hillquit as unpatriotic.

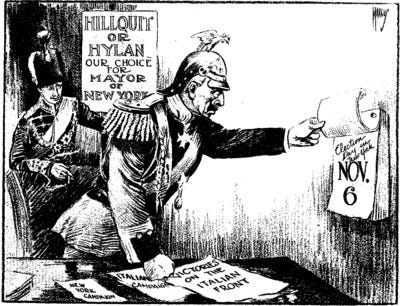

Fear of growing support for socialism drove many of the candidates to direct their campaigns against Hillquit—a New York Times cartoon even portrayed the German Kaiser watching this election closely, labeling New York City the “New Western Front.” Ultimately, Hillquit lost, and John Hylan, the candidate backed by New York City’s Tammany Hall political machine, prevailed. He would remain the mayor until 1925.

Why is this important today? In 2025—as in 1917—words matter. There has been much attention to semantics and slogans on our own campus, as well as on a city-wide level. At the beginning of the race for the Democratic mayoral nomination, the phrase “Globalize the Intifada” emerged as a point of contention amongst the candidates. Mamdani at first refused to condemn its use. Democratic politicians from around the country called him out as they vehemently oppose the phrase, given its association with violence against Jews. Mamdani argued the phrase’s nuances, declared his personal abstention from it, then finally condemned it outright.

What can we learn from discussions about the nuances of this phrase? I believe it teaches us about the importance of language, which is understood differently by various groups. People often do not recognize what many Israelis and Jews experience when they hear the term “Intifada.” Literally translated as “uprising,” the term was often used by both the Israeli public and terrorist groups (Hamas, Islamic Jihad, and Fatah) to describe bombings at cafes, hotels, markets, and on buses that murdered hundreds of Israeli civilians. I personally lost a college friend who stepped on the wrong bus in Jerusalem in 1996. For many American Jews, “Globalize the Intifada” is heard as a call to violence here in the United States. It is understood as having inspired one person to murder a couple in Washington D.C., another to attempt to assassinate the governor of Pennsylvania and his family in their home, and a third to kill an 82-year-old in Boulder, Colorado who dared to march for the release of hostages still being held in the tunnels of Gaza.

To be sure, as many on campus have noted, phrases may be objectionable but are still protected speech, and therefore permissible by law. Still, I hope we might all condemn anyone who, while demonstrating, would fly a Confederate flag or burn a cross in a public campus space (an event that actually took place on the South Lawn in 1924). These examples of protected speech would be deeply disturbing to members of our community, no matter the demonstrators’ intention.

Why should there be any exceptions? Language can be permissible under the First Amendment yet still terrifying to our peers. Avoiding language and actions that make anyone at Columbia feel threatened is not only central to building a strong, diverse campus community; it is critical in order to build a functioning body politic.

On Tuesday, the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) reported that 26 percent of Columbia students surveyed believed that “using violence to stop someone from speaking on campus is acceptable, at least in rare cases.” These alarming findings remind us that Hillquit was on to something over a hundred years ago. As he attempted to build a broad coalition to reshape the city, he made clear to all that rhetoric or actions that flirt with violence must be condemned. Words have meaning and context. Careful use of language is a vital tool for living together in diverse, pluralistic communities.

While we may hear phrases we strongly disagree with, we need to be open to decoding those which we may not be familiar with. We need humility to appreciate words that one person might hear as a call to liberation, and another as a call to violence. Indeed, Hillquit may have lost his election, but the party he created and the ideals he stood for still have much to teach us today.

Rebecca Kobrin is the Russell and Bettina Knapp Associate Professor of American Jewish History at Columbia.

The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Sundial editorial board as a whole or any other members of the staff.

For those interested in submitting a response to this article, please contact us at columbia.sundial@gmail.com.