Does Economics at Columbia Promote Unchecked Capitalism?

A response to Bwog’s critique of Columbia’s introductory Principles of Economics course

Few classes outside Columbia’s Core Curriculum have brought students together like Principles of Economics, the introductory level class for the College’s most popular major. It’s quite a well-known course, but some may argue that this popularity is unearned for a class that misleads its students.

In a Bwog article penned last spring, Maggie Aufmuth CC ’27 claimed that Principles of Economics “relies on assumptions that seldom match economic reality.”

“Economic teaching to Columbia undergraduates is lacking in encouraging critical economic thinking and teaching beyond the confines of free-market capitalist dogmas,” she wrote.

This is a bold claim for a then-first-year to make about a department staffed by dozens of celebrated and established PhD economists. However, Aufmuth proposes that the makeup of the class’s students itself is part of the problem—she argues that the class was “full of future finance bros and not economists” for whom “any ‘interest’ in economics as a major comes from their ambitious pursuit to get on Wall Street.”

As someone who aspires to be an economist rather than a “finance bro,” I am also troubled by students’ lack of genuine interest in economic science. It’s an unspoken (and regrettable) truth that many students study economics because Columbia does not offer a true finance major.

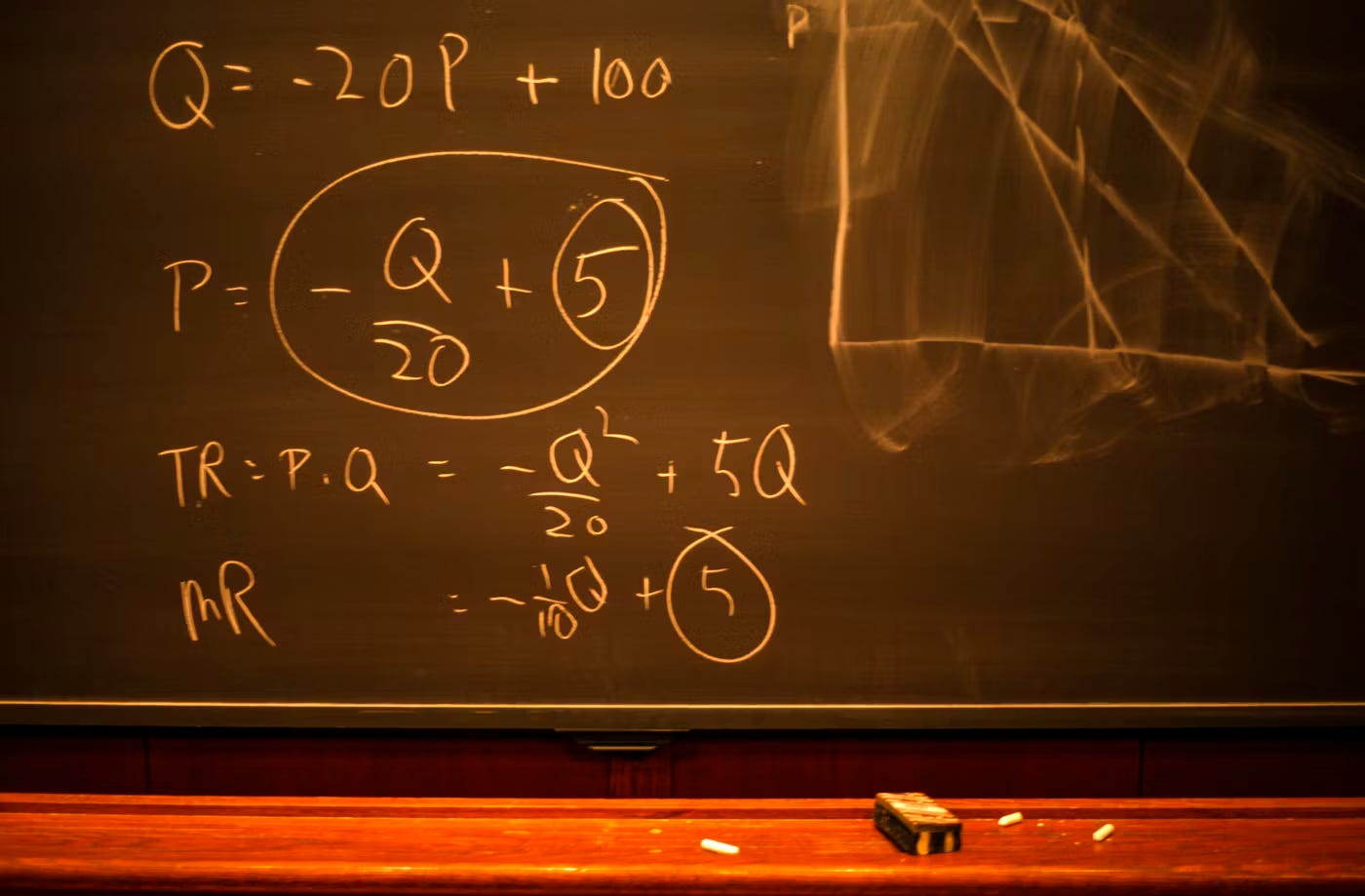

Even so, this problem doesn’t change the fact that the Principles course is exactly what the name suggests: a principles class that introduces students to the most basic theories and models in economics. Of course, Principles of Economics only provides a mere foundation to understand the full complexity of the economic world—an understanding that requires far more studying than a semester’s worth of introductory lectures.

Even with its simplicity, Principles teaches much more than “capitalist dogmas” that reaffirm the free market: It teaches how price ceilings can effectively combat monopolies, that a firm’s optimal level of production often differs from what’s socially optimal, and that the most efficient outcomes are sometimes the result of cooperation, not competition. In short, the class often does teach lessons on when the market falls short and where government intervention may be needed.

Despite these accusations, Aufmuth responds to the purported “capitalist dogmas” of Principles with another dogma: that “market-capitalist assumptions rarely align with reality.”

While some teachings in Principles can seem divorced from reality at times, many students misinterpret them entirely. According to Aufmuth, the class promotes the assumption that “everyone in a market is a rational, free actor with the ability to make decisions,” an idea she takes issue with. However, what economists mean by “rational” is the consumer’s ability to choose the good or service they think will make them the happiest. Aufmuth is correct to claim that every individual may not be rational and free. But for modeling basic economic decision-making, this is a useful and fair assumption to make.

Aufmuth also wrote that the lecture on externalities—which are the indirect effects on a third party from a two-party exchange—“did not reflect how pressing these issues were.” For example, she said that the lecturer framed climate change as “a cost of creating business that could be mitigated by the ‘invisible hand’ free market.” What I think Aufmuth is referring to is the theory that if property rights are well-defined and protected, private parties can come to a socially optimal agreement: a theory that holds true in many cases.

In the example of climate change, countries that produce the most pollution could compensate those most affected, which is both a popular idea and an economically efficient solution. In other words, the “invisible hand” theory that Aufmuth criticizes often helps to support nuanced and progressive solutions to pressing issues.

Not only are ideas such as the “invisible hand” or the “rational consumer” useful assumptions in crafting nuanced economic theories, but they’re also beneficial in crafting arguments that critique and refine those very ideas in the first place. A substantial part of economic literature involves rebuilding and readjusting the assumptions that previous studies rest upon.

Thus, while I agree that the course can afford to dive further into these “market failures,” economics is a social science with different schools of thought that disagree over when and where the free market can succeed, a discussion that is likely beyond the scope of an introductory class.

In short, contrary to her accusations, the course does not endorse dogmatic outcomes. If anything, much of this criticism stems from Principles not endorsing Aufmuth’s underlying dogmas and preconceived beliefs.

A crucial part of learning is continuously refining and adapting one’s beliefs in response to new information—a practice even experts follow. Over time, this process fosters greater nuance in thinking and deepens intellectual humility. But Aufmuth, “having taken AP Macroeconomics,” said she felt “familiar with many of the theories, but disappointed in how they seemed very disconnected from the real world.” Evidently, she felt that this level of experience was enough of a qualification to dogmatically weigh in on an issue that leading economists still grapple with (such as “market-capitalist assumptions” or responding to climate change).

Aufmuth’s piece represents a broader problem—that first-years often walk into introductory classes with very passionate beliefs and react with disbelief and denial when presented with ideas that contradict their own. Ivy League schools are no strangers to this kind of first-year naivety. These reactions are a byproduct of admitting highly accomplished students who have so deeply internalized their success that they struggle to embrace new perspectives.

I don’t mean to blindly defend the teachings of the economics department, or to say that we shouldn’t be critical and inquisitive in our approach to coursework. In fact, Columbia needs more economics students who, like Aufmuth, are genuinely interested in economic theory and are already exposed to some of the literature.

As a social science, economics should always be taught in the context of human impact. However, an introductory course such as Principles can’t even come close to addressing the debate over which policies, assumptions, and dogmas are correct. There’s no ultimate “truth” in economics, and scholarly debate between economists has always been lively.

It’s important to wrestle with and even push back on the ideas we’re taught in class, but that starts with having good-faith conversations with professors and TAs, and accepting that we will often be wrong. This is the spirit of the learning process. After all, students shouldn’t arrive at any class expecting to have their existing worldviews reaffirmed. Instead, students are expected to consider alternative theories and more complex understandings of reality, even if that means starting with the basics.

Mr. Baum is a sophomore at the School of General Studies and the Jewish Theological Seminary, studying economics and Jewish history.

As a Game Theory Economist out of the University of Chicago, the neo-liberal school of thought is grossly outdated. Ideas like rational expectations, general equilibrium, and utility maximization are myths. The field of complexity economics and Agent-based models behave very differently based on the integration of a multi-disciplinary thinking that draws from social psychology, physics, computational mathematics, and chaos theory. We embraced these myths to make our unsophisticated mathematical methods prove our pre-conceived concepts of how economies functioned. There must be a comprehensive rework of how we teach undergraduate economics (for those majoring in economics with the intention to become real economists). Economics must be taught on an interdisciplinary basis to actually teach the truth. Economies are dynamic complex systems and must be treated as such.