Do You Even Care About Palestinians?

Feminism, intersectionality, and the appropriation of Palestinian suffering

As a student of Middle Eastern heritage, I condemn any violence in the region, whether by U.S. forces, terrorist groups, or corrupt governments, and I stand in support of the Palestinian people because I recognize their humanity. Because I view people in the Middle East and Muslim world as fellow humans first, I hope to one day see long-term stability and prosperity in Palestine and a fully democratic region devoid of extremism.

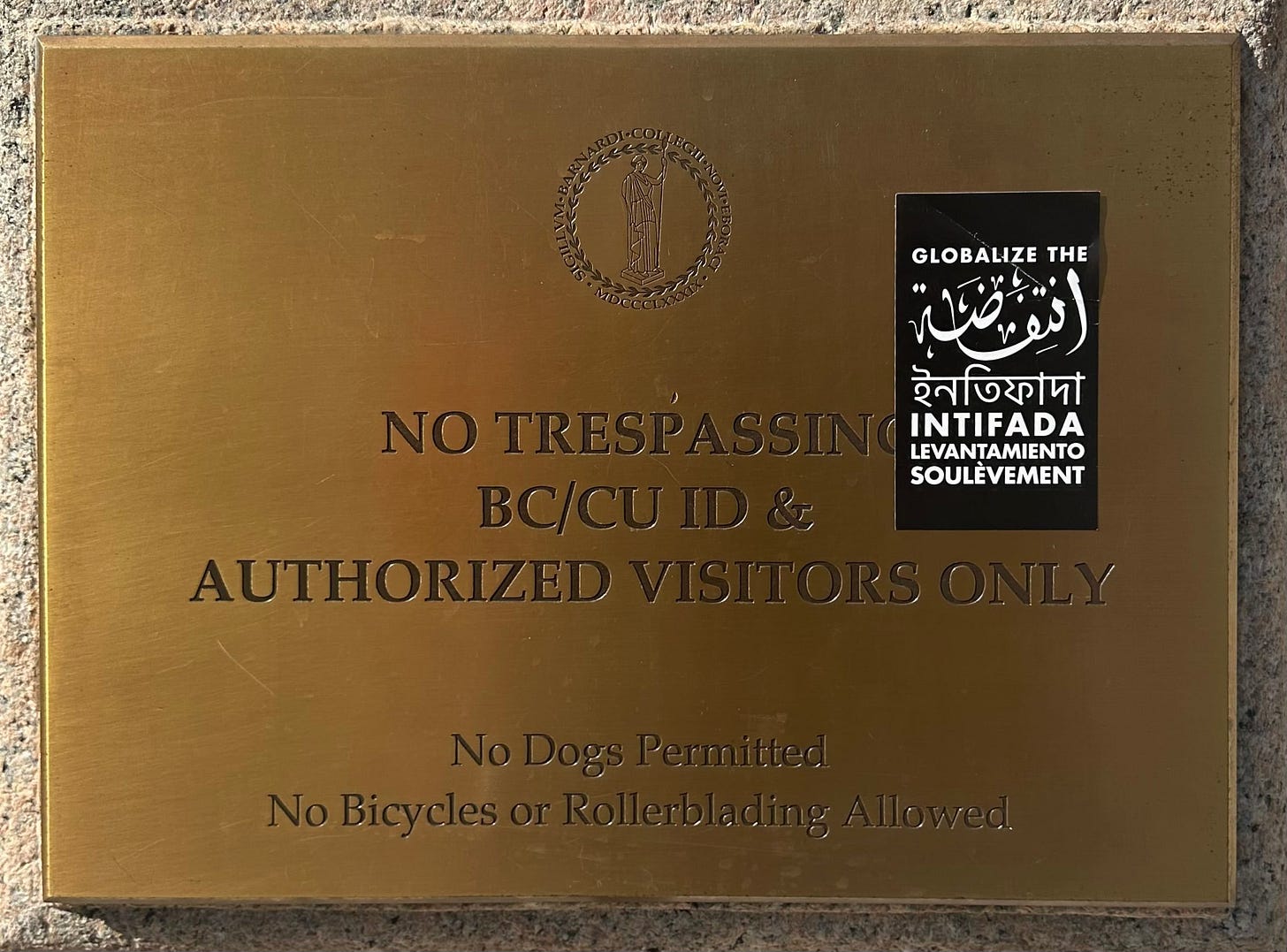

It’s no surprise, given Columbia’s “activist Ivy” identity, that students have continuously advocated for the Palestinian cause since the start of the war. However, as I’ve witnessed the outpouring of support from pro-Palestinian students, I became confused about why this seems to be the issue of our time. The discussion of why we must rally behind Palestinian suffering has become polluted.

On February 2, protestors interrupted Barnard President Laura Rosenbury’s inauguration and leveled accusations at her, including being “a representative of genocide” and not caring enough “about the women in Gaza.” To me, this is a bizarre charge against Rosenbury. As an administrator of an American college, Rosenbury cannot control how many Palestinian civilians Israel kills, whether President Biden signs aid for Israel into law, or the fate of women in Gaza. Even if Rosenbury met the demands of Students for Justice in Palestine and CU Apartheid Divest, including allowing faculty to use departmental webpages for political statements and calling on the Biden administration to support a ceasefire, it’s unclear how that would stop “genocide.” Somehow, this left-wing feminism has ignored Rosenbury’s background as a feminist legal scholar and role as president of a women’s college. Instead, whether you’re a true feminist is contingent on what you do to minimize, in a war thousands of miles away, the number of civilian casualties, which happen to include many women. Palestinian rights have now become women’s rights, and to be a proper Western feminist, according to the activists, you must support the Palestinian state.

Even more bizarre is many feminists’ lack of acknowledgment of Hamas’ rape of Israeli women on October 7 or the generally abhorrent treatment of women by Hamas and the Palestinian Authority. Some even go as far as outright supporting any anti-Israeli resistance group, such as Hamas, Hezbollah, and the Houthis, funded by the notoriously anti-women Iranian regime. To be clear, I support the Palestinian people and their right to self-determination and safety; I also condemn, as a woman from the Middle East, the treatment of the majority of women under certain oppressive governments. I am disappointed that feminists at this school seem unable to do the same.

In previous decades, the shared struggle between the Palestinian cause and feminists, anti-racists, and other civil rights movements was justified. The fundamental principle then and now that connects social justice issues in the West to Palestinian liberation is intersectionality, formalized by Columbia Law professor Kimberlee Crenshaw in 1989.

Palestinian solidarity in Western activist spaces took off in the 60s and 70s during the Civil Rights Movement. In 1970, an advertisement in the New York Times by the Committee of Black Americans for Truth about the Middle East sympathized with the Palestinians because “they are struggling for self-determination and an end to racist oppression.” They also reference the shared “anti-colonial” struggles in “Vietnam, Mozambique, Angola, Brazil, Laos, South Africa, and Zimbabwe,” uniting themselves with these groups against the common enemy of “American imperialism.” Palestinian leaders like Yasser Arafat promoted the idea that just as Americans should advocate for black liberation, they should also fight for Palestinian independence and Vietnamese freedom because all oppressed people are connected by one shared cause. While “racist oppression” and “American imperialism” aren’t explicitly connected, it is true that at that time, minority groups were experiencing oppression many would say was akin to colonialism.

While the idea of a shared thread of oppression may have been justified in the 70s, in 2024 the usage of intersectionality to understand Palestinian suffering bears little resemblance to how it was used during the Civil Rights Movement. Now, because issues such as climate change, women’s rights, and queer issues are under attack from American imperialist forces (or just white men), there is a common struggle that both college leftists and Palestinians feel.

For example, Jewish Voice for Peace writes on their website:

We are committed to support of the Palestinian struggle against Israeli occupation, apartheid, and racism, which is bound up with our analysis of its intersection with the struggles of students of color, student survivors of sexual assault, and all others who on campus fight against oppression, whether imperialism, racism, patriarchy, police violence, or other systemic inequities.

This kind of thinking is not grounded in reality—issues like “sexual assault” of students and “police violence” in America bear no connection to the Israel-Hamas War. Simply put, the lives at stake and the level of brutalization in Gaza mandate that we separate the Palestinian cause from unrelated social justice issues in America.

Yet, according to JVP, social justice issues are inseparable from the Palestinian struggle. Statements like these suggest that for many college leftists, Palestinian rights are a key issue because they believe that the Palestinian struggle and students' feelings of oppression are inextricably related and therefore of equal relevance.

Framing Palestinian humanitarian crises through digestible and low-stakes American social justice issues commodifies Palestinian suffering to be centered around the Western leftist (often “liberal white women”) rather than the Palestinian people. By imposing Western-centric academic gender discourse on the severe women’s rights issues in Gaza, proponents of intersectional theory hope to join in on the oppression as they, too, then can claim that what’s going on in Palestine is harming them.

Take for example what feminism means for Western leftists versus Middle Eastern women. Western feminists fight against the patriarchy, the gender wage gap, and gender-based discrimination. Middle Eastern women are still fighting against mandatory hijab laws, rape-marriage exoneration laws, and seek economic independence from their fathers and husbands. Western leftists should spend more time acknowledging the reality of feminism in the Middle East and should reflect on whether their movement truly supports women’s rights in the region.

This detachment from reality from activists who lead privileged Western lives suggests that for many, the political utility of a cause is more important than the people it affects. When the reality is politically inconvenient, most leftists don’t bother to rally behind the cause: Few Western feminists care enough to advocate for real women’s rights issues in the Middle East because that would mean admitting that it isn’t always “U.S. imperial forces” that create instability and harm women.

Western leftists’ deliberate misunderstanding of Middle Eastern women comes down to their rejection of “colonial feminism.” According to them, colonial feminists use the language of “liberating women” by stereotyping the region and its men as backward and oppressive, thereby justifying Western invasion and occupation. Although any stereotype is harmful, the real struggle for women’s rights in the Muslim world cannot be written off as a simple imperialistic narrative. This logic is just as problematic since it categorizes basic progress and human equality as a Western product. Regardless, most leftists avoid talking about the realities of being a woman in the region as that would mean admitting that the anti-Western “indigenous” forces that they so fiercely advocate for—which often include brutal terrorist militias—are the ones hurting actual women there.

Viewing the humanitarian crisis in Gaza through the lens of women’s rights also clouds the true cause of Palestinian women’s suffering. A women’s rights issue should be rooted in gender-based discrimination or oppression. The killing of Palestinian women in Gaza should not constitute a feminist issue—they suffer by and large because they are Palestinian, not because they are women. Yes, women in Gaza are facing problems men are not, but the same could be said about every other identity group in Gaza given the dire nature of the crisis. Men, women, and children are all suffering because they are being denied their most fundamental human right: the right to life. The discourse often seems to reduce the Palestinian struggle to a “feminist issue,” and then limits feminism to include only Western-privileged elite college feminism. As a result, advocating for Palestine has lost its meaning.

Westerners and the rest of the world should advocate for Palestine by connecting to Palestinians through our shared humanity, not through disconnected political movements or insulting claims of “shared oppression.” When pro-Palestinian activists muddle the Palestinian cause with other issues, whether that be a rejection of the West, hatred for Israel, or feminist decolonization, the arguments serve an ideological agenda more than they help save real human lives.

Palestinians have the right to a movement whose supporters recognize the sanctity of their lives, not because their lives are politically convenient for Western leftists but because they are humans in suffering. If our humanity isn’t reason enough to be pro-Palestinian, then maybe the movement’s intentions aren’t truly with the Palestinians.

Ms. Chaudhry is a sophomore at Columbia College studying history. She is a staff editor for Sundial.

Hi Imaan, I am an Israeli Columbia student. I enjoyed your piece. I come from a pro-Palestinian family; we always voted far-left in Israeli elections, one of my first memories is a peace protest, and conversations among my friends and cousins since October 7 has been centered on how do we solve this issue and build the best future possible for Palestinians. But I’ve been incredibly baffled by the conversation on campus, which seems nothing like the reality I know on the ground. Like, try to tell the Arab Jewish side of my family, who are still bitter about being expelled from Iraq, that they’re colonizers, and see how far you get. I think you captured an important aspect of that. If you want to positively change reality you have to have an accurate model of it. I’d love to talk to you one day, I also think we’ll have plenty to debate.

A refreshing perspective thank you. I am truly dismayed at the level of ignorance and cult like group think displayed by the self-proclaimed “Pro Palestinian” protesters. Can you be pro Hamas and pro-Palestinian? There is a fetishizing of Palestinian suffering. Keep thinking and keep writing. You can legitimately go further in your critique. SIPA 84